"Building Our Monuments' Video art by Jessy de Abreu on the evolution of The Black Archives12/7/2020

The Black Archives is an Amsterdam-based historical archive for conversations, activities, and literature from Black and other perspectives that are often overlooked elsewhere. The Black Archives documents the history of black emancipation movements and individuals in the Netherlands, and consists of unique book collections, archives, and artifacts that are the legacy of Black Dutch writers and scientists. The approximately 3,000 books in the collections focus on racism and race issues, slavery and (de-)colonization, gender and feminism, social sciences and development, Suriname, the Netherlands Antilles, South America, Africa and more.

We refuse to let the European master narrative control our archives. We refuse that it dominates our memories, thoughts, and emotions. Our peaceful efforts for non-western narratives has often been met with (racial) violence. This video, based on own documentations from 2016–2018, shows how we cherish times of joy, pleasure, and laughter in a world that does not wants us to keep smiling. These moments become sacred to us as we hope that they will last forever. Monument is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Het Nieuwe Instituut.

0 Opmerkingen

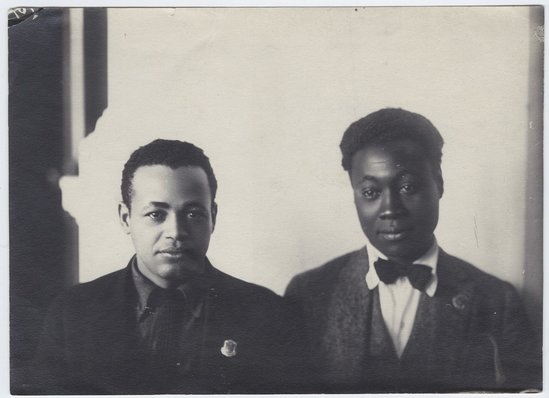

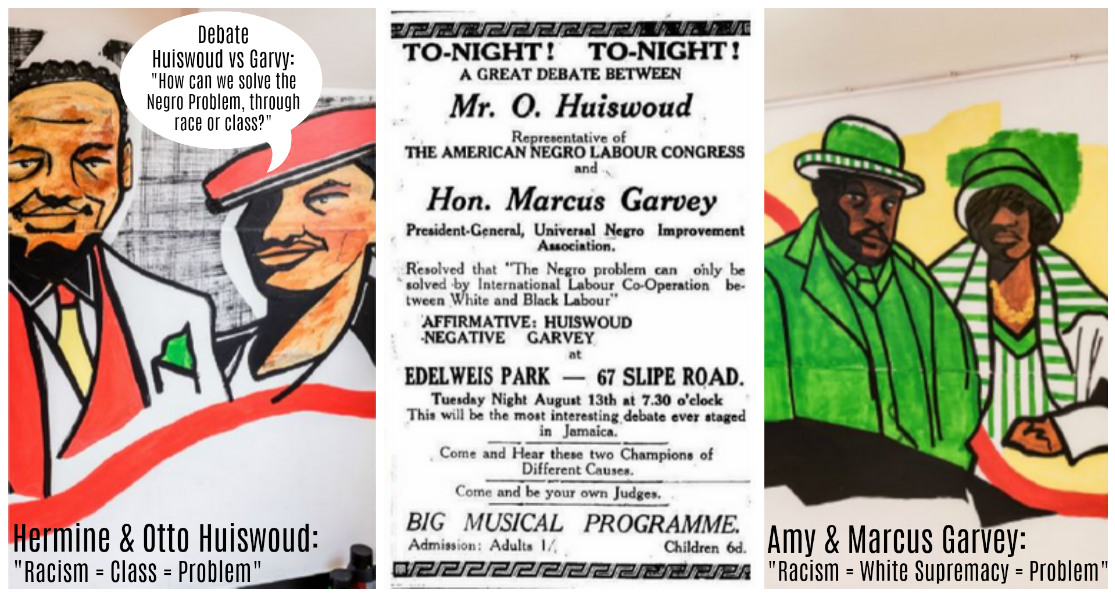

A hidden history of Pan-Africanism: the debate between Garvey and Huiswoud, is it still relevant?12/2/2020 This blog was originally written in Dutch and published on January 24th 2018 The discovery of a historic treasure: The Black Archives This week marks the two-year anniversary since we moved from the “Verhalenkamer” in North Amsterdam to the building of the “Ons Suriname” association (English: “Our Suriname”). To be exact, we entered this historic building on the 23rd of January 2016. In a room on the third floor of the building, we found a collection of books and documents. We did not know exactly what the documents contained, but the room was a big mess. It was full of old boxes and cabinets that, because of the thick layers of dust, gave the impression that they had fallen into oblivion in recent decades. However, we urgently needed space for our books so we made a deal with the association: If we helped them clean up the space, we could place our books alongside their documents. However, while we were busy bringing order to the chaos, we came across extraordinary books and documents. A Time magazine from 1963 with James Baldwin on the cover, program booklets by Keti Koti, emancipation commemorations from the 50's and when we found a book by the famous poet Langston Hughes with his signature, we realized we had stumbled upon a treasure. Many of the treasures came from boxes with the name 'Huiswoud' written on them. Part of the collection appeared to have been collected by Hermine and Otto Huiswoud. This is how our search for the origin of these archival documents and the extraordinary story of the Huiswouds began. A search for the story of Hermine and Otto Huiswoud: Forgotten black revolutionaries Otto Huiswoud was born in 1893. His father had worked as an enslaved person under the Dutch colonial rule. Otto was a curious boy and, at the age of sixteen, he ended up as a student of a captain on a ship that had the Netherlands as its final destination. However, he would not reach this final destination immediately because he would first come ashore in New York. In New York, he soon came into contact with socialist literature and people who were politically active like Hubert Harrison, an African American with roots in the Caribbean island of St. Croix who came to be known as "the Voice of Harlem Radicalism”. It did not take long before Huiswoud himself became politically active. In 1919 he was the only black co-founder of the Communist Party of America (CPUSA). The party was founded shortly after the Russian Revolution, when the socialist party split up. Otto was also active in the African Blood Brotherhood, a black militant organization that aimed to improve the position of African Americans. Hermina Huiswoud was born in British Guiana in 1905 and migrated with her family to New York in 1919. Otto and Hermina met in New York and would spend the rest of their lives together. In 1922 Otto travelled as a delegate on behalf of the CPUSA to the Fourth World Congress of the Comintern in Moscow. Together with the Jamaican poet Claude McKay, he worked to get what they called the “Negro Question" on the party's agenda. Black communists and “the Negro question” Many black activists, such as the Huiswouds and McKay, drew inspiration from communist ideology and the October Revolution in Russia of 1917. Communists pursued a world revolution in which workers would overthrow the imperial powers and the system of capitalism. Based on socialist theory, black communists argued that "the Negro question"- the oppression of people of African origin around the world - was fundamentally an economic problem in which black people were used as a source of cheap labor by the capitalist class. [1] For example, Huiswoud argued at the congress in Moscow: “Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way back in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way back in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” – Huiswoud, 1922 They saw organizing and mobilizing black people in the U.S. and colonies in Africa and the Caribbean as an essential step to bringing about the world revolution. In addition, they saw solidarity between black and white workers as a necessary means for orchestrating this revolution. However, competition between workers and the legacy of slavery that spread into vicious forms of racism and discrimination divided the working class according to black communists. For example, black workers were often not admitted to unions, were paid less for the same work and there was segregation of various public and private facilities such as schools, buses and swimming pools. During this period, racism was violent and manifested itself in the lynching practices that systematically terrorized black communities. It was a period during which white supremacy took explicit and violent forms in the US and European powers had most of the African continent, South America and the Caribbean under colonial control. A more subtle form of racism was also present in the North of the US. Practices such as exclusion in the labor market and the housing market were widespread. There was little organized resistance. After all, resistance was dangerous. Watch this lecture by Dr. Hakim Adi, author of the book Pan-Africanism & Communism Click here to edit. Marcus Garvey and de UNIA Although many black radicals who wanted to fight for freedom found their salvation in communism, there were also other ideas and movements. The most prominent black emancipation movement that emerged in the same period was the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) led by Marcus Garvey. Garvey had already started in Jamaica but founded a division in the United States in the same year that the October Revolution took place in 1917. A direct cause was the bloody "East St. Louis riot" in which 40 black Americans were killed by racist violence caused by a conflict between black and white workers. White workers were afraid that black workers would take over their jobs in the aluminum industry. [1] Unlike the black communists, Garvey did not believe that "the Negro Question" was fundamentally an economic issue of class struggle that required solidarity with white workers. Garvey held the idea of “race first”. As an advocate of black nationalism, he believed that black people could be emancipated by pursuing political, economic and cultural independence. “Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad” was his motto. With the famous Black Star shipping line, he aimed to promote trade between different black communities and through the newspaper "the Negro World" he managed to reach millions of black people. Garvey is seen as one of the icons of Pan-Africanism, an ideology and movement based on the idea that people of African origin have common interests worldwide and therefore need to unite. Watch a documentary about Marcus Garvey here: Garvey's UNIA has had the largest mass movement of black people in history so far, at its peak the movement had an estimated one million members in the US, Caribbean and Europe. Because of personal and political circumstances, including fierce battles with black communists and security services, the influence of Garvey and the UNIA declined relatively quickly. He was convicted of fraud in 1923 and deported to Jamaica in 1927. The UNIA never recovered, but Garvey's immense ideological influence has been evident in the vision of black emancipation movements to this day. His words are immortalized in Bob Marley's famous song, Redemption song:"Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds!” The black star on the Ghanaian flag is co-inspired by Garvey's Black Star line. Although Garvey did not pursue a world revolution like the black communists, his vision and movement revolutionized the minds of many black people who, after centuries of racist indoctrination, learned to be proud of themselves, their skin color and their African background. The big debate: Garvey vs. Huiswoud During our research we came to the extraordinary discovery that Huiswoud and Garvey knew each other. Although they both pursued the emancipation of black people, they had opposing views on how emancipation could be realized. In 1929 Otto and Hermina visited a number of Caribbean and South American countries on behalf of the Comintern: Trinidad, Haiti, Colombia, Suriname, British Guiana and Jamaica. In Jamaica, a UNIA congress, which Garvey tried to revive, took place during the same period. Huiswoud saw this as an opportunity to challenge Garvey to a public debate in the lion's den: In Garvey’s homeland and during his own congress. Garvey accepted the debate. The debate was announced in the Jamaican newspaper “the Gleaner”. Huiswoud would defend the following statement: "The Negro problem can only be solved by International Labor Co-Operation between White and Black Labor". Garvey was against it. In an account of the debate in the same newspaper a few days later, entitled "How can the Negro problem be solved?", the vision of Huiswoud and the black communists was clearly described: “Mr. Huiswoud moved for the affirmative. He said that he believed that the negro problem could only be solved through international cooperation of the workers, black, white and yellow the issue meant the relationship of the black and white, living side by side, the relationship of master and slave. It was an exploitation of negroes by the white ruling class with the only one object in view the securing of super-profits. (…) The Negro problem was definitely a class problem, fundamentally a class one and not a race one, for race served to intensify the situation, and gave an impetus to the further exploitation of the negro.” Garvey, on the other hand, defended his position that black people should not only focus on labor but also to raise capital so that their own empire could start. Garvey won the debate, but according to archival documents, Huiswoud managed to win over a number of people. He returned a year later, in 1930, to meet black workers but was seen by the authorities as a "communist agitator" and was heavily opposed. In 2018, we aim to investigate this debate and the various movements in the black radical tradition. Relevance of the debate

Although the debate between Garvey and Huiswoud took place 90 years ago (1927), the issue of "the Negro Question" is still very relevant in 2017. Worldwide, from the African continent, to the United States, Europe and the Caribbean, the majority of people of African origin are at the bottom of the social ladder. On a daily basis, people of African origin are still being dehumanized with the modern form of slavery in Libya and the countless Africans who die during their crossing from the continent to Europe as tragic lows. Despite the fact that certain goals, from both Huiswoud and Garvey, have been achieved, the vast majority of people of African origin live in appalling conditions. After the wave of decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s, in which both black nationalism and communist-inspired emancipation movements played an important role, most African and Caribbean countries became politically independent. Economically, however, many countries are still in a dependent position where raw materials are exploited by western companies that make large profits while the majority of the population does not benefit from them. Politically, in most African and Caribbean countries, "black leaders" are in power, but the old colonial power structures seem to have remained unchanged under their rule. In many Caribbean and African countries, a powerful class of black people has emerged. In many cases, there is a small group that enjoys the wealth while the masses live in poverty or have to die with very limited resources. For example, research showed that there are more than 160,000 people who own assets of more than $1 million while gross national income per capita is still relatively low and about half of the children in the sub-Saharan region live on $1.90 a day. [1] [2] The average income in 'Western' countries is higher, which reduces extreme poverty, but income and wealth inequality is still huge. Researchers say it would take 228 years to close the wealth disparity between black and white families in the US. [3] In the New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander describes how, despite the accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement, a significant portion of the African American population is stuck in a "racial underclass". Despite the fact that an upper class of wealthy African Americans has emerged, the system of mass incarceration, "the New Jim Crow" perpetuates racial inequality. There are currently more African Americans in prison or probation than there were enslaved in 1850, and a quarter of the African American population lives below the poverty line. Although the extreme wealth and income inequality in the Netherlands is less severe than in the US and extreme poverty is rare, there is also racial inequality here. According to CBS,12% of Surinamese Dutch and 20% of Caribbean Dutch people live in poverty compared to 5% of people of Dutch origin. The figures are harder to find about people from the African continent. During our study trip, the events in Charlottesville once again reminded us in a violent way that the problem of white supremacy is not yet a thing of the past. On the contrary, the racism and white supremacy that was so openly displayed in the days when Huiswoud and Garvey were alive seems to have made a comeback. "The Negro Question" is as relevant as it was 90 years ago, but what can we learn from the lives of the various movements that have fought? Who was right from a historical perspective, Garvey, Huiswoud or was there in each of their visions a kernel of truth? How is it that many of us know Garvey but have never heard of Huiswoud and |

The Black Archives BlogArchieven

Juni 2024

|

Openingstijden/Opening TimesWoensdag/Wednesday 11.00 - 17.00 uur

Donderdag/Thursday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Vrijdag/Friday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Zaterdag/Saturday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Onze nieuwe locatie in Amsterdam Zuidoost is geopend. Neem contact op via de pagina contact voor rondleidingen buiten het programma. We moved to South East Amsterdam. Contact us via the page contact for tours outside our program. |

(Rolstoel)toegankelijkheid/Accessibility

Momenteel beschikt The Black Archives niet over een speciale ingang en lift voor personen met een fysieke beperking en voor rolstoelgebruikers.

At this moment, The Black Archives does not have a special entrance or lift for person of disability. |

RSS-feed

RSS-feed