|

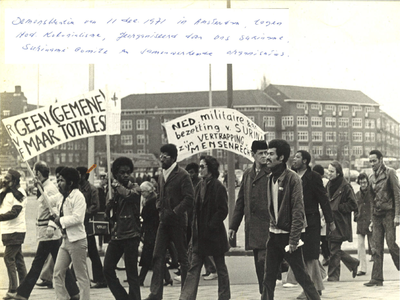

Door: Mitchell Esajas* De vondst van een historische schat: The Black Archives Deze week is het exact twee jaar geleden dat wij van de Verhalenkamer in Amsterdam-Noord verhuisden naar het pand van Vereniging Ons Suriname. Op 23 januari 2016, om precies te zijn, betraden wij dit historische pand. In een ruimte op de derde verdieping van het pand scheen ook een collectie boeken en documenten te liggen. Wat er precies lag wisten we niet, de ruimte was echter een grote chaos. Het lag vol met oude dozen en kasten die door de dikke lagen stof de indruk gaven dat ze de afgelopen decennia in de vergetelheid waren geraakt. We hadden echter dringend ruimte nodig voor onze boeken dus we maakten een deal met de vereniging: als hij hen hielpen de ruimte op te ruimen konden wij onze boeken erbij plaatsen. Terwijl we bezig waren orde in de chaos te scheppen kwamen we echter bijzondere boeken en documenten tegen. Een oude Time magazine uit 1963 met James Baldwin op de cover, programma boekjes van Keti Koti emancipatie herdenkingen uit de jaren ’50 én toen we een boek van de beroemde poet Langston Hughes met zijn handtekening vonden wisten we dat we een schat hadden gevonden. Veel van de schatten kwamen uit dozen waar de naam ‘Huiswoud’ op stond geschreven. Een deel van de collectie bleek verzameld te zijn door Hermine en Otto Huiswoud. Zo begon onze zoektocht naar de herkomst van deze archiefstukken en het uitzonderlijke verhaal van de Huiswouds.

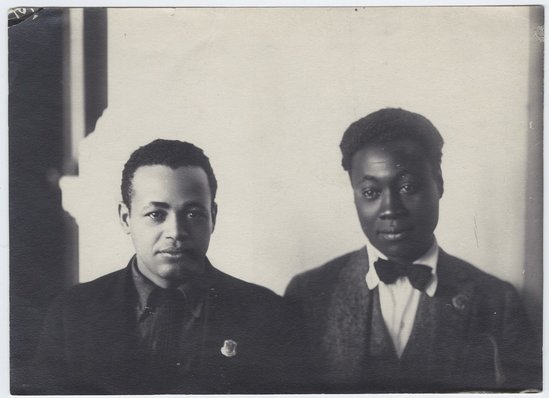

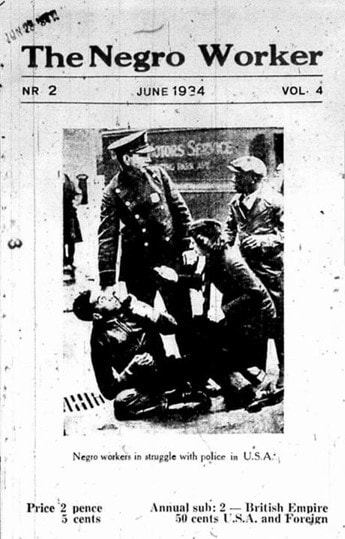

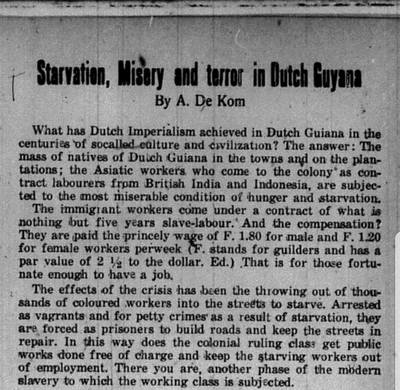

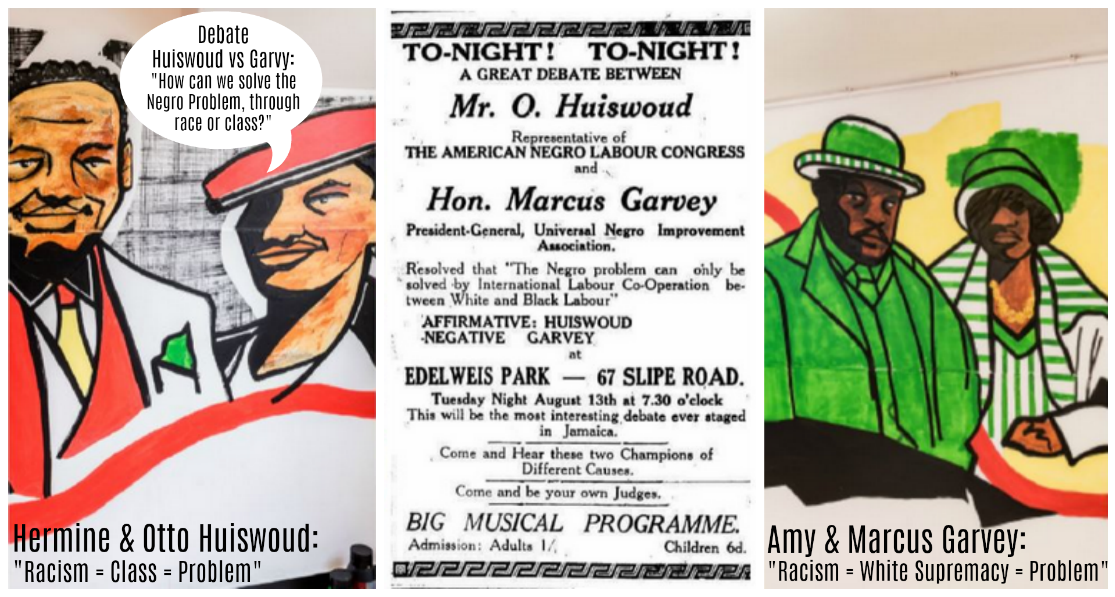

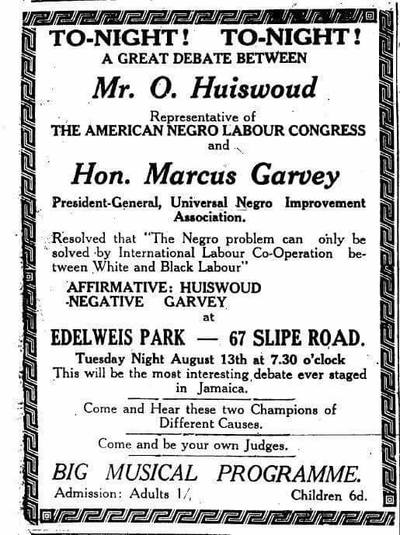

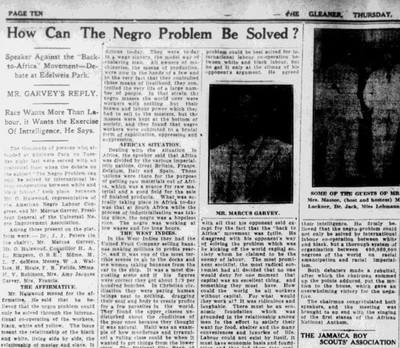

Een zoektocht naar het verhaal van Hermine en Otto Huiswoud: vergeten zwarte revolutionairen Otto Huiswoud is geboren in 1893, zijn vader heeft nog als tot slaaf gemaakte moeten werken onder het Nederlandse koloniale bewind. Otto was een nieuwsgierige jongen en belandde op zestienjarige leeftijd als matroos in de leer van een kapitein op een schip dat Nederland als eindbestemming had. Hij zou deze eindbestemming echter niet direct bereiken omdat hij in New York aan wal trad. In New York kwam hij al snel in aanraking met socialistische literatuur en mensen die politiek actief waren zoals Hubert Harrison, een Afro-Amerikaan met wortels in het Caribische eiland St. Croix die bekend kwam te staan als “the Voice of Harlem Radicalism”. Het duurde niet lang totdat Huiswoud zelf ook politiek actief werd. In 1919 was hij de enige zwarte medeoprichter van de Communist Party of America (CPUSA). De partij ontstond toen er na de Russische Revolutie een splitsing gebeurde binnen de socialistische partij. Ook Otto actief in de African Blood Brotherhood, een militante zwarte organisatie die als doel had om de positie van Afro-Amerikanen te verbeteren. Hermina werd geboren in 1919 in Brits-Guyana en migreerde in 1919 met haar familie naar New York. Otto en Hermina ontmoetten elkaar in New York en zouden de rest van hun leven met elkaar delen. In 1922 reisde Otto als afgevaardigde namens de CPUSA naar het Vierde Wereldcongres van de Comintern in Moskou. Samen met de Jamaicaanse poet Claude McKay spande hij zich in om wat zij “the Negro Question” noemden op de agenda van de partij te krijgen. Otto Huiswoud en Claude McKay, 1922 in Moskou Zwarte communisten en “the Negro question” Vele zwarte activisten, zoals de Huiswouds en McKay, haalden inspiratie uit de Oktoberevolutie in Rusland van 1917 en uit communistische ideologie. Communisten streefden een wereldrevolutie na waarin arbeiders de imperiale machten en het systeem van kapitalisme omver zouden werpen. Op basis van socialistische theorie stelden zwarte communisten dat “the Negro question”, de onderdrukking van mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst in de hele wereld, fundamenteel een economisch probleem was waarin zwarte mensen als een bron van goedkope arbeid werden gebruikt door de kapitalistische klasse.[1] Zo betoogde Huiswoud het volgende tijdens het congres in Moskou: “Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way back in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way bak in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” – Huiswoud, 1922 Otto Huiswoud, Langston Hughes en een Afro-Amerikaanse delegatie in de Sovjet Unio in de jaren '30 Het organiseren en mobiliseren van zwarte mensen in de VS en kolonies in Afrika en het Caribisch gebieden zagen ze als een essentiële stap om de wereldrevolutie tot stand te brengen. Daarnaast zagen ze solidariteit tussen zwarte en witte arbeiders als een noodzakelijk middel om te revolutie tot stand te brengen. Concurrentie tussen de arbeiders en de erfenis van slavernij dat zich uitte in vicieuze vormen racisme en discriminatie verdeelde de arbeidersklasse echter volgens zwarte communisten. Zo werden zwarte arbeiders vaak niet toegelaten tot vakbonden, kregen ze minder betaald voor het zelfde werk en was er sprake van segregatie verschillende publieke en private voorzieningen zoals scholen, bussen en zwembaden. Het racisme uitte zich in deze periode op zeer gewelddadige manier door de lynchpraktijken waarmee zwarte gemeenschappen stelselmatig geterroriseerd werden. Het was een periode waarin witte suprematie expliciete en gewelddadige vormen aan nam in de VS en waarin Europese mogendheden het grootste deel van het Afrikaanse continent, Zuid-Amerika en het Caraïbische gebied onder koloniale controle had. Het vond echter ook plaats in de vorm van subtielere vormen van racisme zoals uitsluiting op de arbeidsmarkt en de woningmarkt in het Noorden van de VS. Er was nog weinig sprake van georganiseerd verzet, verzet was immers levensgevaarlijk. Bekijk hier een lezing van dr. Hakim Adi, auteur van het boek Pan-Africanism & Communism De Russische revolutie en de communistische visie dat een eeuwenoud imperium omver had geworpen en openlijk opriep tot bevrijding van alle onderdrukte volkeren bood voor vele zwarte activisten dan ook een aanlokkelijk vergezicht. Zwarte radicalen zagen de wereldrevolutie als een kans om zichzelf en de gekoloniseerde gemeenschappen waar ze uit voortkwamen te bevrijden. Huiswoud was één van de vele zwarte radicalen die zich in deze periode aansloot bij de Communistische beweging om de strijd aan te gaan voor de wereldrevolutie. In de periode voor de Tweede Wereldoorlog wist hij, tezamen met zijn vrouw Hermina, een prominente carrière als professioneel revolutionair op te bouwen waarbij hij onder meer de wereld rond rees om zwarte vakbondsbewegingen op te zetten en met elkaar te verbinden. Zo werd Otto, nadat George Padmore uit de partij was gezet, voorzitter van de International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW). Als redacteur van hun blad, the Negro Worker, had Otto contact met zwarte activisten in de VS, Europa, het Afrikaanse continent, het Caraïbische gebied en in Latijns-Amerika. Zo schreef Anton de Kom in 1923 een artikel getiteld “Starvation, Misery and Terror in Dutch Guiana". Ook stonden er boeiende artikelen in over de Scottsboro Case, de Congo, de invasie van Ethiopië door de Italianen en meer. Marcus Garvey en de UNIA Hoewel vele zwarte radicalen wilden strijden voor vrijheid hun heil vonden in het communisme waren er ook andere visies, stromingen en bewegingen. De voornaamste zwarte emancipatie beweging die in dezelfde periode opkwam was de Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) onder leiding van Marcus Garvey. Garvey was reeds in Jamaica begonnen maar richtte in hetzelfde jaar dat de Oktoberrevolutie plaatsvond, in 1917, een divisie in de Verenigde Staten op. Een directe aanleiding was de bloedige “East St. Louis riot” waarbij 40 zwarte Amerikanen door racistisch geweld waren omgekomen, nota bene vanwege een conflict tussen zwarte en witte arbeiders. Witte arbeiders waren bang dat zwarte arbeiders hun banen in de aluminium industrie zouden overnemen.[1] In tegenstelling tot de zwarte communisten geloofde Garvey niet dat “the Negro Question” fundamenteel een economische kwestie van klassenstrijd was waarbij solidariteit met witte arbeiders vereist was. Bij Garvey stond “race first”, als voorvechter van zwart nationalisme geloofde hij dat zwarte mensen geëmancipeerd konden worden door politieke, economische en culturele onafhankelijkheid na te streven. “Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad” was zijn motto. Met de fameuze Black Star shipping line beoogde hij de handel tussen verschillende zwarte gemeenschappen te bevorderen en middels de krant “the Negro World” wist hij miljoenen zwarte mensen te bereiken. Garvey wordt gezien als één van de iconen van het Pan-Afrikanisme, een ideologie en beweging gebaseerd op het idee dat mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst wereldwijd gezamenlijke belangen hebben en zich daarom dienen te verenigen. [1] Ida B Wells schreef hierover? The renowned journalist Ida B. Wells reported in The Chicago Defender that 40–150 African-American people were killed during July in the rioting in East St. Louis.[14][18] The NAACP estimated deaths at 100–200. Six thousand African-Americans were left homeless after their neighborhood was burned. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_St._Louis_riots Bekijk hier een documentaire over Marcus Garvey: Garvey’s UNIA heeft tot nu toe de grootste massabeweging van zwarte mensen in de geschiedenis gehad, op het hoogtepunt had de beweging naar schatting een miljoen leden in de VS, het Caribische gebied en Europa. Wegens persoonlijke én politieke omstandigheden, waaronder felle strijd met zwarte communisten en veiligheidsdiensten, zijn Garvey en de UNIA relatief snel weer ten onder gegaan. Hij werd in 1923 veroordeeld wegens fraude en in 1927 naar Jamaica gedeporteerd. De UNIA is er nooit bovenop gekomen maar de immense ideologische invloed van Garvey is tot vandaag de dag zichtbaar geweest in de visie van zwarte emancipatiebewegingen. Zijn woorden zijn vereeuwigd in het bekende lied van Bob Marley, Redemption song: "Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds!” De zwarte ster op de Ghanese vlag is mede-geïnspireerd door de Black Star line van Garvey. Hoewel Garvey geen wereldrevolutie nastreefde zoals de zwarte communisten heeft zijn visie en beweging voor een revolutie in de geest van vele zwarte mensen gezorgd die na eeuwenlange racistische indoctrinatie leerden trots op zichzelf, hun huidskleur en hun Afrikaanse achtergrond te zijn. Muurschilderingen van Brian Elstak / Foto's: Maartje Strijbis Het grote debat: Garvey vs. Huiswoud Tijdens ons onderzoek kwamen tot de bijzondere ontdekking dat Huiswoud en Garvey elkaar kenden. Hoewel ze allebei de emancipatie van zwarte mensen nastreefden hadden ze tegengestelde visies op de manier waarop de emancipatie gerealiseerd kon worden. In 1929 bezochten Otto en Hermina in opdracht van de Comintern een aantal Caribische en Zuid-Amerikaanse landen: Trinidad, Haiti, Colombia, Suriname, Brits-Guyana én Jamaica. In Jamaica vond in dezelfde periode een congres van de UNIA, die Garvey nieuw leven in probeerde te blazen, plaats. Huiswoud zag de kans schoon om Garvey tot een publiek debat uit te dagen in het hol van de leeuw, in zijn thuisland en tijdens zijn eigen congres. Garvey accepteerde het debat. Het debat werd groots aangekondigd in de Jamaicaanse krant, the Gleaner. Huiswoud zou de volgende stelling verdedigen: “The Negro problem can only be solved by International Labour Co-Operation between White and Black Labour". Garvey stond er tegen over. In een verslag van het debat in dezelfde krant enkele dagen later, getiteld “How can the Negro problem be solved?”, stond de visie van Huiswoud en de zwarte communisten duidelijk beschreven: “Mr. Huiswoud moved for the affirmative. He said that he believed that the negro problem could only be solved through international cooperation of the workers, black, white and yellow The issue meant the relationship of the black and white, living side by side, the relationship of master and slave. It was an exploitation of negroes by the white ruling class with the only one object in view the securing of super-profits. (…) The Negro problem was definitely a class problem, fundamentally a class one and not a race one, for race served to intensify the situation, and gave an impetus to the further exploitation of the negro.” Garvey verdedigde daarentegen zijn positie dat zwarte mensen zich niet slechts moesten richter op arbeid maar ook kapitaal moesten vergaren zodat hun eigen imperium konden starten. Garvey won het debat maar volgens archiefstukken wist Huiswoud in het hol van de leeuw toch een aantal mensen voor zich te winnen. Hij keerde een jaar later, in 1930, terug om zwarte arbeiders te ontmoeten maar werd door de autoriteiten als “communist agitator” gezien en tegengewerkt. In 2018 beogen wij nader onderzoek te doen naar dit debat en de verschillende stromingen in de zwarte radicale traditie. De relevantie van het debat Hoewel het debat tussen Garvey en Huiswoud 90 jaar geleden, in 1927, plaatsvond is het vraagstuk, “the Negro Question”, anno 2017 nog erg relevant. Wereldwijd, van het Afrikaanse continent, tot de Verenigde Staten, Europa en het Caraïbische gebied, bevindt het gros van de mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst zich aan de onderkant van de maatschappelijke ladder. Op dagelijkse basis worden mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst nog gedehumaniseerd met de moderne vorm van slavernij in Libië en de talloze Afrikanen die de dood vinden tijdens hun overtocht van het continent naar Europa als tragische dieptepunten. Ondanks het feit dat bepaalde doelen, van zowel Huiswoud als Garvey, zijn gerealiseerd leeft het overgrote deel van de mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst onder erbarmelijke omstandigheden. Na de dekolonisatiegolf in de jaren ’50 en ’60, waarin zowel zwart nationalisme als communistische geïnspireerde emancipatiebewegingen een belangrijke rol speelden, zijn de meeste Afrikaanse en Caraïbische landen politiek onafhankelijk geworden. Economisch gezien zijn vele landen echter nog in een afhankelijke positie waarin grondstoffen worden geëxploiteerd door westerse bedrijven die grote winsten maken terwijl het gros van de bevolking er niet van profiteert. Politiek gezien zijn in de meeste Afrikaanse en Caribische landen “zwarte leiders” aan de macht, maar de oude koloniale machtsstructuren lijken ook onder hun bewind weinig verandert te zijn. In vele Caraïbische en Afrikaanse landen is er weliswaar een kapitaalkrachtige klasse van zwarte mensen ontstaan. In vele gevallen is er een kleine groep die van de rijkdom geniet terwijl de massa in armoede leeft of met zeer beperkte middelen moet zien te overleden. Zo bleek uit onderzoek dat er meer dan 160,000 mensen zijn die een vermogen van meer dan $1 miljoen bezitten terwijl het bruto nationaal inkomen per hoofd nog relatief laag is en ongeveer de helft van de kinderen in de regio onder de Sahara in extreme armoede, $1.90, per dag leven.[1] [2] Het gemiddelde inkomen in ‘westerse’ landen is hoger waardoor extreme armoede minder voorkomt maar de inkomens- en vermogensongelijkheid is nog gigantisch. Volgens onderzoekers zou het 228 jaren duren om de kloof in vermogensongelijkheid tussen zwarte en witte gezinnen in de VS te dichten.[3] In the New Jim Crow beschrijft Michelle Alexander hoe, ondanks de overwinningen van de Civil Rights Movement, een aanzienlijk deel van de Afro-Amerikaanse bevolking vast zit in een “raciale onderklasse”. Ondanks het feit dat er een bovenklasse van vermogende Afro-Amerikanen is ontstaan reproduceert het systeem van massa-incarceratie, “the New Jim Crow” raciale ongelijkheid in stand. Er zijn momenteel meer Afro-Amerikanen in de gevangenis of in de reclassering dan dat er in 1850 tot slaaf gemaakt waren en een kwart van de Afro-Amerikaanse bevolking leeft onder de armoedegrens. Hoewel de extreme vermogens- en inkomensongelijkheid in Nederland minder sterk is dan in de VS en extreme armoede nauwelijks voorkomt is er ook hier sprake van raciale ongelijkheid. Zo leeft, volgens het CBS, 12% van de Surinaamse Nederlanders en 20% van de Caraïbische Nederlanders in armoede ten opzichte van 5% van de mensen van Nederlandse origine. Over mensen van het Afrikaanse continent zijn de cijfers minder makkelijk te vinden. Tijdens onze studiereis werden we door de gebeurtenissen in Charlottesville wederom op een gewelddadige manier herinnert dat het probleem van witte suprematie nog niet tot het verleden behoort. Integendeel, het racisme en de witte suprematie dat zo openlijk getoond werd in de tijd dat Huiswoud en Garvey leefden lijkt een comeback te hebben gemaakt. “The Negro Question” is net zo relevant als 90 jaar geleden maar wat kunnen we leren van de levens van de verschillende bewegingen die hebben gestreden? Wie had gelijk vanuit historisch perspectief, Garvey, Huiswoud of zat er in elk van hun visies een kern van waarheid? Hoe komt het dat velen van ons Garvey wel kennen maar nog nooit van Huiswoud hebben gehoord en wat is de legacy van Hermine en Otto Huiswoud in Nederland? De komende maanden gaan wij verder met ons onderzoek naar Hermine en Otto Huiswoud. Op 27 januari zal historicus Hakim Adi een lezing geven op basis van zijn boek Pan-Africanism and Communism waarin onder meer het debat tussen Garvey en Huiswoud is belicht. Bezoek voor meer informatie onze website www.theblackarchives.nl. * Een andere versie van dit artikel werd eerder gepubliceerd via IISR. Lees hier de reactie van Sandew Hira.

Read more:

2 Opmerkingen

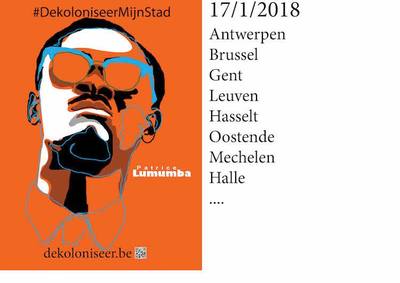

Op 17 januari 2018 is het precies 57 jaar geleden dat de Congolese vrijheiddstrijder Patrice Lumumba werd vermoord. Patrice Lumumba was één van de veelbelovende antikoloniale leiders die voortkwam uit de dekolonisatie golf in de jaren '50 en '60 op het Afrikaanse continent. In 1958 richtte Lumumba de Congolese National Movement (Mouvement National Congolais; MNC) op waarmee hij vocht voor de onafhankelijkheid van Congo dat nog een Belgische kolonie was. Koning Leopold van België had de Congo tot zijn persoonlijke bezit verklaart en een van de meest gewelddadige koloniale systemen ingevoerd dat tussen 1880 en 1910 tenminste 10 miljoen Congolezen het leven had gekost. Lumumba werd na een intense onafhankelijkheidsstrijd, dat toen nog een Belgische kolonie was, de eerste premier van de Republiek Congo. Op 20 juni 1960 was de Belgische koning Boudewijn in Congo om de onafhankelijkheid te officieel te 'overhandigen', Lumumba had geen toestemming gekregen om te spreken. Hij onderbrak echter de toesprak van de koning en gaf zelf een legendarische en krachtige speech waarin hij zich zeer kritisch uitliet over de voormalige kolonisatoren. De speech staat bekend als de "Bloed en Vuur" speech, lees en bekijk hieronder de speech: "Dit was ons lot gedurende tachtig jaar koloniaal regime, onze wonden zijn nog te vers en te pijnlijk om ze uit ons geheugen weg te wissen. Wij hebben dwangarbeid gekend in ruil voor lonen die veel te laag waren om voldoende te kunnen eten, ons waardig te kleden of te wonen of om onze kinderen als dierbaren te kunnen opvoeden. Wij hebben spot, beledigingen, slagen gekend die we ‘s ochtends, ‘s middags en ‘s avonds moesten ondergaan, omdat wij 'negers' waren. Wij zijn getuige geweest van het afschuwelijke lijden van degenen die veroordeeld waren voor hun politieke standpunten of godsdienstige overtuigingen: verbannen in hun eigen land was hun lot nog slechter dan de dood." (...) "Samen zullen wij sociale rechtvaardigheid vestigen en ervoor zorgen dat iedereen een rechtvaardige vergoeding voor zijn arbeid ontvangt. Wij zullen de wereld tonen wat de zwarte man kan realiseren wanneer hij in vrijheid kan werken, en wij zullen van Congo het stralend voorbeeld voor heel Afrika maken." Deze speech werd hem niet in dank afgenomen door de (neo)koloniale autoriteiten. Hij werd als een gevaar voor de gevestigde orde gezien. Vele Westerse entiteiten hadden, en hebben vandaag de dag nog steeds, belangen in het grondstoffen rijke Congo. Lumumba werd binnen een jaar, onder druk van neokoloniale machten, vermoord. Bekijk de documentaire "The Assissination of Patrice Lumumba": De Huiswouds, Pan-Afrikanisme en Lumumba In de expositie Zwart en Revolutionair is te lezen dat de laatste activiteit waar Otto Huiswoud zich mee bezig hield, voor hij zelf in 1961 overleed, een actie rondom de moord op Lumumba was. Reeds in 1931 schreef Otto Huiswoud in The Negro Worker een kort artikel getiteld "The Congo Uprising" over een opstand tegen de koloniale autoriteiten. Hij schreef: "Once again revolt is sweeping the Belgian Congo. In 1925, again in 1928 the revolt of the native masses was ruthlessly drowned in b lood by Belgian imperialism. But despite the slaughter, the terrible oppression of the native masses of the Congo has once more for ced them into revolt. (...) The Belgian imperialists are trying their best to crush the rising tide of rebellion, but the revolts of the native masses in Africa today have far greater possibilities of success than ever before." De Huiswouds probeerden in de jaren '30 middels het krantje The Negro Worker en de International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (International Trade Union Committe of Negro Workers) zwarte mensen in de diaspora en in het continent te mobiliseren voor een anti-koloniale en anti-imperialistische revolutie. In die zin waren ze onderdeel van een vroege pan-Afrikaanse beweging, een beweging die het gezamenlijke belang van mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst inzag. Vanuit de Pan-Afrikaanse visie wisten ze een netwerk op te bouwen van zwarte activisten, intellectuelen en leiders in Noord-Amerika, het Caribsich gebied, Europe en het Afrikaanse continent. Toen de dekolonisatiegold in de jaren '50 en '60 op gang kwam volgden de Huiswouds de ontwikkelingen op de voet. Zo werd er in het krantje dat er in de jaren '50 vanuit Vereniging Ons Suriname, de Koerier, onder leiding van Otto Huiswoud geschreven over de onafhankelijkheid van Ghana, Marokko en de strijd tegen apartheid in Zuid-Afrika. Hermie onderhield in deze periode nauw contact met de Afro-Amerikaanse dichter Langston Hughes. Hughes schreef een prachtig gedicht over Lumumba getiteld "Lumumba's Grave". Het gedicht is in de expositie in een werk van kunstenaar Raul Balai te lezen. Is Pan-Afrikanisme nog relevant? Vanaf het begin van de 20e eeuw waren zwarte activisten wereldwijd verbonden via het Pan-Afrikanisme. Velen, zoals Hermina en Otto Huiswoud, die zich identificeerden met het Pan-Afrikanisme sympathiseerden ook met het communisme of socialistische ideologieën. Is dit in de 21e eeuw nog relevant? Wat kunnen we van deze geschiedenis leren anno 2018 waarin de meeste Afrikaanse en Caribische landen onafhankelijkheid hebben verworven maar nog met grote economische en politieke problemen kampen? Hoe zit het met de verbinding tussen mensen uit de Afrikaanse diaspora in de Nederlandse context? Is er voldoende verbinding of is men vooral gericht op de eigen groep van herkomst? In de week van 22 januari gaan we in gesprek over Pan-Afrikanisme tijdens enkele evenementen:

"Voor Hand in Hand is er een direct verband tussen structureel racisme en kolonialisme. De eeuwenlange uitbuiting door de koloniale mogendheden heeft nog steeds nefaste gevolgen voor de machtsverhoudingen in de wereld. De grootschalige propaganda die deze uitbuiting goedpraatte door de gekoloniseerden te ontmenselijken (vaak letterlijk door er slaven van te maken) werkt nog steeds door in allerlei racistische denkbeelden en vooroordelen over de "andere", of ze nu in het Globale Zuiden wonen of in Europa. Deze koloniale machtsverhoudingen én denkbeelden zijn een belangrijke oorzaak van het huidige structurele racisme in onze samenleving. Ze creëren nog steeds een onderklasse van mensen die ongelijk behandeld worden omwille van hun huidskleur of afkomst. Zowel in de dagelijkse omgang als op het vlak van wonen, werken, onderwijs, enz. (...) De propaganda voor het koloniale systeem werd onder meer ondersteund via vele koloniale standbeelden en straatnamen. Zij monopoliseren de publieke ruimte in het discours over het koloniale verleden en verheerlijken de kolonisatoren als helden. Het is meer dan tijd om dit straatbeeld te dekoloniseren en de stemmen laten horen van mensen en organisaties met een migratie-achtergrond. Tijd om met ons allen in het reine te komen met het koloniaal verleden. En ook tijd om samen onze verantwoordelijkheid op te nemen." Wil je meer weten over Lumumba? Check dan deze artikelen:

On Sunday January 14th I was invited to share some of my thoughts about Martin Luther King Jr. and the anti-racism movement at the Martin Luther King Day Jr event organized by Humanity In Action based on the title of one of dr. King's books and speeches "Where do we go from here?". This is an excerpt of my (way too long) speech: In the summer of 2016 I was one of the John Lewis Fellows to learn about the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta, the place where dr. King was born and bred. Our dormitory was on a walking distance from the place where he was born, where he preached “Ebenezer Baptist Church” and where dr. King and 1000s of people from the Civil Rights Movement had marched. I bought the book during the John Lewis Fellowship when we visited the Martin Luther King memorial center in Atlanta 2 years ago but I never really had time to read it until now. I've taken some time over the past few days to read it and listen to the speech. It is fascinating fascinating to read and hear how relevant his thoughts still are, even for the situation in the Netherlands. During the Fellowship, however, we learned in practice about the relevancy of dr. Kings work and words. A few days after the start of the program there were nationwide #BlackLivesMatter demonstrations to protest the police killings of #AltonSterling and #PhilandoCastille. Together with my other fellows and thousands of other people I marched on the streets where dr. King and those active in the movement and marched 50 years earlier and I learned about another side of dr. King, especially from the black women who lead the fellowship program.

The dr. King we all know "I have a dream"

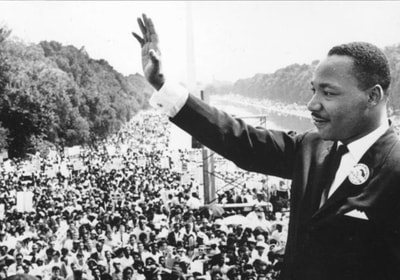

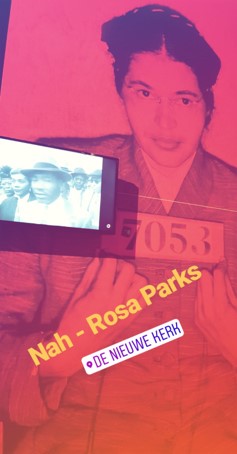

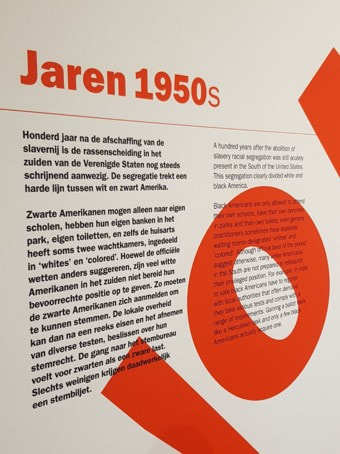

People all around the world learn about dr. King as the icon of the Civil Rights Movement and non-violent resistance. Almost everyone is familiar with his legendary ‘I have a dream speech’, given during the March on Washington in 1963. The familiar story most of us learn via mainstream media goes a little bit like this: the United States, the home of the brave of the free, was built on the backs of black people who were exploited as slaves for centuries. The Southern states relied heavily on the slave economy and the profitable cotton industry in contrast to the more industrialized North. When the Civil War broke out between Northern and Southern states the abolishment of slavery was one of the key reasons. On December 6th, Abraham Lincoln signed the emancipation declaration which abolished the institution of slavery. Southern states who still relied on forced labor tried to maintain the exploitation of black people by institution legalized racial segregation through Jim Crow laws. Most of us are familiar with the shocking images of signs “whites only” reflecting the harsh daily reality which reduced people racialized as black to a form of second class citizenship. Black and white children were not allowed to go to the same schools and they were not allowed to drink from the same water fountains. Black people had to sit on the back of the bus until Rosa Parks said “Nah” and refused to stand up. She sparked the development of a mass movement. Martin Luther King Jr. became the face and leader of the nonviolent resistance movement after the illustrious Montgomery bus boycot. White extremists from the Ku Klux Klan, fuelled by white supremacist ideology, attacked and terrorized black people who dared to stand up for their rights but many ‘liberal’ white people supported the movement. During the Freedom Rides even white allies got viciously attacked and sacrificed their lives for the freedom of black people. Despite the racist violence from the KKK, racist police and white supremacist politicians, despite being verbally and physically attacked dr. King held fast on to his philosophy of nonviolent resistance. In 1963 dr. King gave his legendary I have a dream speech during the March on Washington, he lead the march on Selma leading to the historical victories of the Civil Rights Movement, legislation which abolished racial segregation and gave black people the right to vote. Martin Luther King Jr. became the icon of the movement and is still being praised all over the world. Although, dr. King, deserves much praise and recognition for his courageous and exceptional work, this simplified and “Santa clausified” version of the story of dr. King does injustice to what King actually fought and sacrificed his life for. It can even be employed to damage to the work of does who fight and work against racism today.

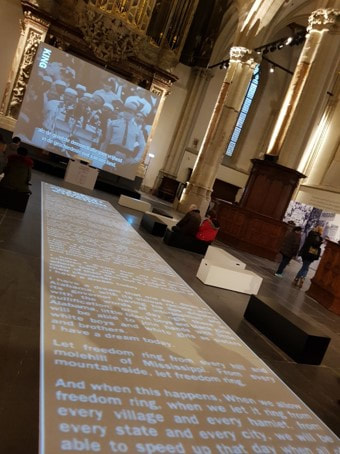

An example: the Santa clausification of dr. King in de Nieuwe Kerk Amsterdam

This simplified reconstruction of dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement, is being reproduced all over the world by commercial enterprises, NGOs, in children’s books and in exhibitions such as the exhibition “We have a dream” in De Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam. Already expecting the mainstream version of the story of Martin Luther King jr. I still decided to visit the day before the Martin Luther King Day Jr. event. The exhibition is described on the website as follows: “We Have a Dream is an exhibition about three world-renowned figures who profoundly influenced the course of the twentieth century: Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela. They were ordinary people who led extraordinary movements against racial discrimination and social injustice. All three became role models around the world but also drew fierce criticism and opposition. Two were assassinated because of their ideas and activism.” #1 The Santa clausified King vs. The Radical King The exhibition consists of several panels with text, images and videos of Martin Luther King Jr. and a few historical documents. Although the makers have been quite creative in using the space it confirmed my doubts and expectations. The exhibition includes all of the ingredients of the Santa clausified version of dr. King. The first ingredient is the reduction of King’s struggle to a fight against Jim Crow segregation and for integration around the “I have a dream speech”. This speech can arguably be seen as one of the best, of not the best, public speech in modern history. The rhetorical excellence combined with beautiful work way dr. King preached on the Washington Mall continue to inspire people. There is more to dr. King though. Over the past years several books and articles have been published about the evolution of King’s vision towards more radical vision. Dr. West edited a selection of speeches in the book “The Radical King” which reflect his thoughts on issue such as, white supremacy, war and capitalism. More recently, Brandon M. Terry, wrote an essay in which he stated that King has become a “mythic figure of consensus and conciliation, who sacrificed his life to defeat Jim Crow and place the United States on a path toward a “more perfect union” , whose image is even being used by conservatives. It is not a coincidence that the white supremacist in chief Trump was able to symbolically celebrate dr. King in the same week that he called Haiti and several African nations ‘shithole countries’. In the mainstream Santa clausified version of dr. King he seems be be frozen in the time period between the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955 and the legendary march on Selma in 1965. In reality, however, King’s politics and vision evolved, especially after the victories of the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965). Over the past few years activists from different networks such as #BlackLivesMatter have organized events and campaigns to ‘desanitize the legacy of dr. King’. Zo startte Ferguson Action de hashtag #ReclaimMLK om de kant van King te laten zien die we vaak niet in mainstream media en educatie zien. Many of the problems dr. King fought against continue to plague not only the United States but oppressed people around the world: global economic inequality continues to keep people trapped in poverty, over the few decades the US has continued to wreak havoc around the world with its violent military might and over the pasy few years the #BlackLivesMatter movement showed the world how white supremacy continues to kill innocent and unarmed black men, women and LGTQ+ people. Ferguson Action network, an activist network which arose after the police murder of Mike Brown , stated this about reclaiming the legacy of dr. King: “Our movement draws a direct line from the legacy of Dr. King. Unfortunately, Dr. King’s legacy has been clouded by efforts to soften, sanitize, and commercialize it. Impulses to remove Dr. King from the movement that elevated him must end. We resist efforts to reduce a long history marred with the blood of countless women and men into iconic images of men in suits behind pulpits.” Opal Tometi, one of the co-founders of the #Black Lives Matter network, who visited Amsterdam several years a go tweeted this:

The King Philosophy: Triple Evils

If you develop an exhibition, give a talk or present the work and legacy of dr. King without mentioning (elements of) his fundamental philosophy of the triple evils you are not doing justice to what he sacrificed his life for. In the dominant narrative the story is that King solely focused on the nonviolent fight against racism whilst in reality he fought just as hard against poverty, economic inequality and the increasing militarism of the United States. Dr. King’s philosophy was based on what he called “the Triple Evils” of Poverty, Racism and Militarism: “forms of violence that exist in a vicious cycle. They are interrelated, all-inclusive, and stand as barriers to our living in the Beloved Community. When we work to remedy one evil, we affect all evils.” King called the United States “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today” in his controversial “Beyond Vietnam” speech in 1967 as he became more critical and aware of the relation between America’s foreign policy and war and inequality in the US.[1] In his “Where do we go from here?” speech he stated: “A nation that will keep people in slavery for 244 years will "thingify" them and make them things. And therefore, they will exploit them and poor people generally economically. And a nation that will exploit economically will have to have foreign investments and everything else, and it will have to use its military might to protect them. All of these problems are tied together.” In the same speech and book he argued for a basic income for all as a solution for persisting economic inequality and poverty. If you leave the exhibition “We Have a Dream”, however, without doing further research you’ll think that dr. King’s dream had come trough before he was assassinated, black people had won the right the vote and were allowed to sit in the front ánd back of the bus right?

#2 Reduce racism to white supremacist violence

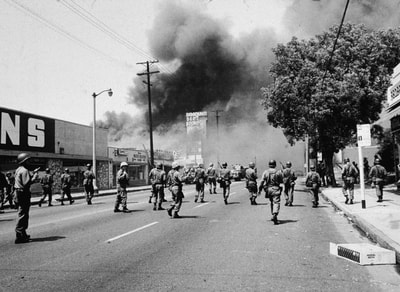

A second ingredient of the Santa clausification is the reduction of racism and white supremacy to the violence of white extremists like the KKK and Jim Crow segregation in the South. Equating racism and white supremacy to these specific manifestations of these dehumanizing systems erase or play down the other more covert and subtle forms of racism. On one of the panels in the exhibition “We have a dream” the issue of racism is explained. As expected it only mentions Jim Crow segregation in the South: segregation in the busses, schools and public spaces such as parks. Not one word was written about the North suggesting that the North was free of racism and dr. King did not think about racism in the rest of the country or the rest of the world. Ta-Nehisi Coates described racism in the North in his seminal essay ‘a case for reparations”: “In the North, legislatures, mayors, civic associations, banks, and citizens all colluded to pin black people into ghettos, where they were overcrowded, overcharged, and undereducated. Businesses discriminated against them, awarding them the worst jobs and the worst wages. Police brutalized them in the streets. And the notion that black lives, black bodies, and black wealth were rightful targets remained deeply rooted in the broader society.” Only a week after the victory of the Civil Rights Act (1965), which gave black people the right to vote, major riots broke out in Watts, Los Angeles. More than 1000 people were left injured, 34 people died and over $3 billion worth of property in today’s money was damaged. The anger which resulted in the riots were fuelled by the cycle of poverty, institutional racism and police violence in this predominantly black area of a Northern city, Los Angeles. Although King did not condone the outbreak of riots he did not blame the people, he blamed the system which caused the anger and despair resulting in the riot.

The danger of this simplification of racism is that it obscures how racism manifests itself differently in different geographical locations and different time periods. And this narrative can be misused to critical thinking about the way racism and white supremacy have continued to evolve and change just like society has evolved and change over time. This narrative is often mobilized in the Dutch context to silence and downplay institutional racism in the country of white innocence. Professor Gloria Wekker described it as follows:

“It encapsulates a dominant way in which the Dutch think of themselves, as being a small, but just, ethical nation; colour-blind, thus free of racism; as being inherently on the moral and ethical high ground, thus a guiding light to other folks and nations. Notwithstanding the many, daily protestations in a Dutch context that “we” are innocent, racially speaking; that racism is a feature found in the US and South Africa, not the Netherlands; that, by definition, racism is located in working-class circles, not among “our kind of middle-class people”; much remains hidden under the univocally and the pure strength of will defending innocence. I am led to suspect bad faith; innocence is not as innocent as it appears to be.” One of the prime examples of white innocence is the most popular national tradition Saint Nicolas. The mythic figure who is accompanied by a black servant, which is in reality often played by white people in blackface to reproduce racist caricatures of black people. Altough many Dutch people claim that it is just an innocent children’s holiday and people should not associate it with racism or a history of slavery and colonialism the reaction on those who critize the tradition shows that the tradition may not be as innocent as people claim. Over the past few years the civil and human rights of anti-zwart piet activists have been violated repeatedly by police, white extremist and even those who claim to be ‘open, liberal or moderate white people’. In 2011 Jerry Afriyie and Quinsy Gario were unlawfully arrested by the police just for wearing a t-shirt stating ‘Zwarte Piet Is Racisme’ at the national Saint Nicolas parade in Dordrecht. In 2014 activists of Kick Out Zwarte Piet, including myself, attempted to organize a nonviolent protest at the Saint Nicolas parade in Gouda. After the mayor ordered us to a location which would make the protest futile we decided to continue our protest in the spirit of King’s vision on civil disobedience. Around 70 people were arrested, Jerry Luther King was arrested violently by the police, many more were left traumatized. Two years later in 2016 200 people were arrested in Rotterdam, some again with violence. In 2017 three busses with transporting anti-zwart piet activist to the North of the Netherlands were dangerously blocked on the high way by white extremists after a white lady named Jenny Douwes publicly called to stop Kick Out Zwarte Piet from exercising there right of freedom of speech and peaceful assembly. After blocking the road she was praised in Dutch mainstream media as a hero and got space in time to state and explain ‘I am not a racist’. The exhbition " We have a dream" does include a short video of scholar Philomena Essed, radio host Andrew Makkinga and anti-zwarte piet activist Jerry ' Luther King' Afriyie (yes, that's his real name), but it fails to make a relation between racism and anti-racism in the Netherland and the rest of the exhbition. When I was there the video was shows on a screen right next to exit and but I was unable to listen to because there was no sound. De Nieuwe Kerk charges 16,- per person, its free for kids aged until 11. so the Santa clausification and commodification of King can be quite lucrative as the institution welcomes thousands of visitors, including a lot of tourists, every week. So the exhibition is a missed opportunity to teach thousands of people not just about the Santa clausified and commercialized version of dr. King but about his radical vision which is still relevant today, also to address racism, economic inequality and militarism in the Netherlands and globally.

#3 The problem with white moderates

Dr. King was well aware of the different manifestations of racism and white supremacy. In the book "Where do we go from here" King critically analysed how it evolved over time from the era of slavery in which pseudoscientific racist theories were used to legitimize the exploitation of black labor to paternalistic behaviour of white moderates who claimed that they believed in equal rights but still acted in a way that revealed that they had internalized the idea of white superiority. He devoted a whole chapter to the problem of ”racism and the white backlash”. After a decade of nonviolent struggle the Civil Rights Movement had made major victories. After several centuries of violent oppression and exploitation of black people he noticed that black people had won the battle legally but in practice the struggle still had to be continued. Whilst a number of white people had joined them in the movement and sacrificed their lives, the backlash of white supremacists grew and segregation persisted to exist. 90% of the schools were still segregated, employment opportunities were still unequal and black people continued to be trapped in poverty in the North and the South. The backlash, however, did not just come from white extremists, King noted that the lack of action of white moderates and liberals was one of the biggest problems, he wrote: “Whites, it must frankly be said, are not putting in a similar mass effort to re-educate themselves out of their racial ignorance. It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the white people of America believe they have so little to learn.” This is also the case in the Netherlands. A key example is a statement Femke Halsema – the former leader of the Green Left party - made recently in an interview about anti-racism in the Netherlands. First, she mobilized the narrative which equates racism to explicit forms of racism such as the Jim Crow laws by using segregation in the busses as an example. Second, she blamed the #MeToo campaigners and anti-zwarte piet activist for ‘exagerrating’ and misusing American concepts such as ‘white privilige: “They prove themselves no service with, for example, the use of the American concept of 'white privilege'. In the Netherlands black people do not have to be in the back of the bus separately. You can not just move a discourse from a country that has had systematic oppression to here, and say to the Dutch: you are doing the same thing. That is not true, and distracts from the racism that is indeed here. If you call everything racism, you can not find the real racists anymore.”

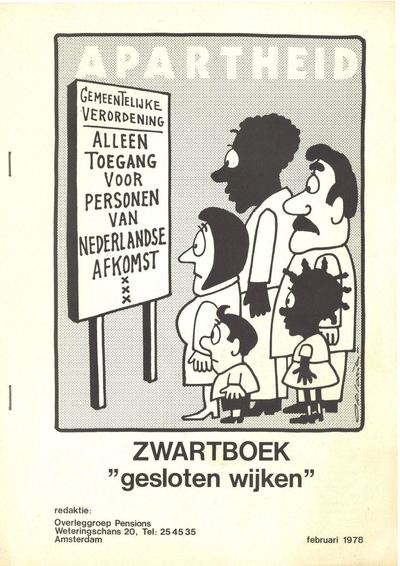

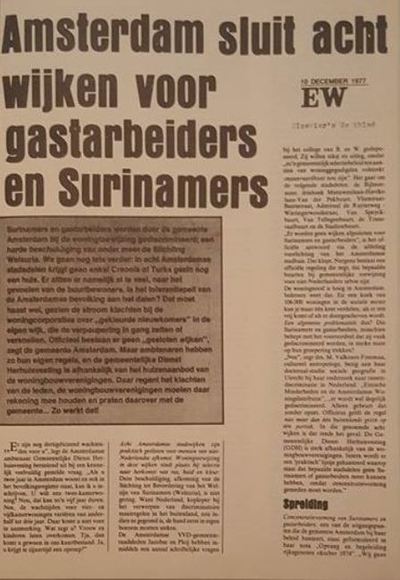

This statement displays the ignorance some ‘white moderates and liberals’ have about the complexity of racism and the different ways it manifests itself. It also shows how the narrative of equating racism to white supremacist violence and systematic racial segregation can be mobilized to silence anti-racist activists. Femke, who probably considers herself committed to justice and equality, is one example of many white liberals who actually throw anti-racist activists under the bus by downplaying these issues in the Dutch context. Over the past few decades much research has been done proving that racism and discrimination are structural problems in different areas of Dutch society. Recent research of criminologist showed that white job applicants with a criminal record have more chances of receiving a positive reaction compared to applicants with a migrant background without a violent offense. Amnesty International criticized Dutch police as ethnic profiling continued to infringe the human rights of Dutch people with a migrant background. Although the Netherlands may not have had a formal system of segregation like the US in until the 1960s, the schools continue to be heavily segregated based on class and ‘ethnicity / race’ between so called ‘black and white schools’. And although the Netherlands did not have formal Jim Crow segregation, it was one of the major European nations involved in the trade in enslaved Africans and colonized several territories in the Americas and Asia. The first enslaved Africans in the United States arrived on a Dutch ship and New York used to be a Dutch colony, hence the name Harlem and Brooklyn. In the 1940s the Dutch fought a violent colonial war to continue its control over Indonesia and Surinam only gained independence in 1975. Most black people only migrated to the Netherlands in the 1970s and they were not welcomed with “Dutch tolerance’, documents from the archives show that certain neighbourhoods in the Netherlands were actually closed of for Surinamese people and people from Turkey and Morocco. White innocence is a myth and these kinds of statements and narratives only help to keep this “fantasy and self deception”, as dr. King would say, alive.

Similarly to dr. King, the story of Rosa Parks is often simplified. She was not just some random lady who one day just decided to resist white supremacy by refusing to stand up for a white man to sit in the back of the bus. She was a trained activist and a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the organizaton that trained Rosa Parks. The Netherlands did not have a Rosa Parks, because there was no Jim Crow segregation. Yet, we did have a Ernestine Comvalius who resisted housing discrimination and was one of the people involved in the LOSON, a movement of Surinamese, who squatted building in Amsterdam Southeast, together with allies of the white squatting movement so Surinamese people and other people of color could have decent housing. We did not have a dr. King and a Civil Rights Movement but we did have several movements and leaders who resisted Dutch colonialism and racism from the early 1920s until today. This history, however, has long remained hidden and silenced because of the dominance of the ‘white innocence’ narrative which is keen to acknowledge racism in the United Stated but remains silence about similar problems within the boundaries of the Dutch nation. That is why The Black Archives developed the exhibition ‘Black & Revolutionary: the story of Hermina and Otto Huiswoud’, a story of an revolutionary activist couple who fought for liberation and equality all around the world including the US and the Netherlands. In fact, Hermina and Otto Huiswoud were in close contact with people who had laid the foundation for the “Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s to 1960s. Activists and scholars such as W.E.B. duBois was a friend of the Huiswouds. Dr. King stated:

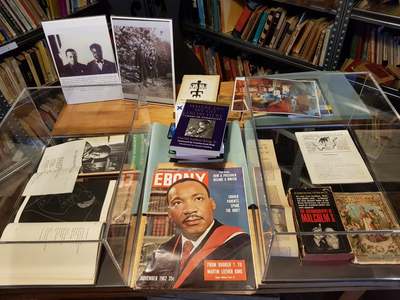

“History cannot ignore W. E. B. DuBois because history has to reflect truth and Dr. DuBois was a tireless explorer and a gifted discoverer of social truths.” In The Black Archives we found exceptional documents and newspaper clippings which were collected by Otto and Hermina Huiswoud about the Civil Rights Movement. As they had lived in the United Stated for a long time and actively fought against racial segregation in the country it was a matter that was very dear to them. This weekend we will put some of the documents and newspaper clippings from the archive on display and during the tours we will pay special attention to documents about the Civil Rights Movement such as the Ebony magazine from 1962 with dr. King on the cover and a newspaper article about the day dr. King visited Amsterdam in 1946. The Santa clausification of Martin Luther King Jr., however, can be used for lucrative business.

Next blog:

In a next blog I will write more about the relevant issues dr. King addressed in his “Where do we go from here” speech and book and some of the lessons we can learn from it for the current anti-racism in the Netherlands. One of the things I’d argue is that we need to complicate our thinking and organizing. We can learn from “the Triple Evils philosophy of dr. King which related racism with militarism and capitalism but this was not complete. It should be expanded to the five evils to include homophobia and sexism. King also addressed the question of Black Power and the necessity of political and economic empowerment of black people and the importance of decolonizing the mind. Additionally, he stressed the importance of building coalitions with people from different backgrounds, especially whites who were prepared to sacrifice something for the greater good. Dr. King said: "In the End, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends." White people, stop appropriating, silencing, sanitizing and Sant clausifying black history. If you want to learn about the more truthful history of King and the Civil Rights Movement, visit The Black Archives and speak out against inequality and oppression in the spirit of King. Not just on Martin Luther King Jr. day but every day. We give tours in The Black Archives and the exhibition Black & Revolutionary every weekend. Where do we go here? Lessen van Martin Luther King voor de anti-racisme beweging in Nederland1/7/2018

Door: Mitchell Esajas, mede-oprichter The Black Archives

Zondag 14 januari zal het Martin Luther King Day event van Humanity In Action plaatsvinden, de titel is dit jaar "Where do we go from here" op basis van een van de befaamde speeches en het gelijknamige boek van Martin Luther King Jr. uit 1967. Ik ben uitgenodigd om wat gedachten te delen over de anti-racisme beweging in Nederland, een grote eer. Afgelopen weekend heb ik tussen de rondleidingen in The Black Archives door even wat archiefstukken van Hermina Huiswoud bekeken. Hermina verzamelde tot ze in 1998 overleed magazines, krantenknipsels en boeken onder meer over de Civil Rights Movement. Één van mijn favoriete vondsten in het archief is een Ebony magazine uit 1962 met Martin Luther King Jr. op de cover. In het magazine lag ook een krantenartikel over Martin Luther King Jr. verborgen uit het Algemeen Handelsblad uit 1964, dr. King gaf die week een lezing in de RAI in Amsterdam tijdens een congres voor Europese baptisten.

De strijd van King is nog steeds nodig

In de zomer van 2015 had ik het privilege om naar Atlanta te gaan voor het John Lewis Fellowship voor een zomer programma over de Civil Rights Movement. Daar kocht ik het boek "Where do we go from here?" van Martin Luther King Jr. in het Martin Luther King Memorial Center, vlak naast de plek waar hij was geboren. Pas nu heb ik echter de tijd om het boek te lezen. Het is fascinerend om te lezen dat veel van de discussies die in de jaren '50 in de VS speelden ook vandaag spelen, zowel in de VS als in Nederland, weliswaar op een andere manier. Tijdens het fellowship zouden we leren over de burgerrechtenbeweging van de jaren '50 en '60. De heftige gebeurtenissen toonden echter dat racistisch geweld in de 21e eeuw nog even actueel was als zestig jaar geleden. Die zomer vonden er massale #BlackLivesMatter protesten plaats na de moorden op twee onschuldige zwarte mannen Alton Sterling en Philando Castille. De strijd die Martin Luther King Jr. en de burgerrechtenbeweging voerden werd voortgezet door een nieuwe generatie activisten, er speelden echter pittige discussies over de strategie en tactiek die voor vooruitgang kon zorgen, lees hier het essay dat ik voor Humanity In Action schreef.

De verzameling van Hermina Huiswoud

Hermina volgde de politieke ontwikkelingen in de wereld op de voet. Omdat Otto en Hermina zelf lang in de VS hadden gewoond en hun leven hadden geweid aan de strijd voor emancipatie van zwarte mensen volgden ze de burgerrechtenbeweging met extra interesse. In de collectie van de Huiswouds vonden we een map met krantenknipsels over de Civil Rights Movement . In de stapel vond ik een mooi artikel over een actie die scholieren uit Amsterdam hadden georganiseerd om solidariteit te tonen met kinderen in Little Rock. In Little Rock, Arkansas, mochten zwarte kinderen in 1957 voor het eerst naar een "geïntegreerde school" nadat de NAACP, één van de prominente burgerrechtenorganisatie, de Brown vs. Board of Education rechtszaak won. Door de gewonnen rechtszaak werd rassensegregatie op scholen verboden. Vele witte mensen in het zuiden van de VS, waaronder de gouverneur van de staat Arkansas wilden houden de de verandering echter tegenhouden. In het boek "Where do we go from here" wijt King een heel hoofdstuk aan de witte weerstand tegen de vooruitgang die de burgerrechtenbeweging aan het boeken was: "The persistence in depth and the dawning awareness that Negro demands will necessitate structural changes in society have generated a new phase of white resistance in North and South, schreef hij. Witte extremisten riepen op om de zwarte kinderen die naar de eerste geïntegreerde school gingen aan te vallen, de gouverneur roep zelfs de Nationale Garde op om de kinderen ervan te verhinderen om naar school te gaan. De toenmalige president Eisenhower stuurde als reactie daarop troepen naar de school om de kinderen onder bescherming naar school te laten gaan. De beelden van dit extreem racistische geweld gingen de hele wereld over en bereikten kennelijk ook kinderen in Amsterdam. Volgens een artikel uit het Parool van 2 oktober 1957 zamelden zo een duizend scholieren uit Amsterdam, o.a. van mijn oude school het Spinoza Lyceum, handtekeningen in om hun solidariteit te tonen met de kinderen in de VS. Ze overhandigden deze handtekening en een petitie aan de Amerikaanse ambassadeur, een mooi voorbeeld van solidariteit. King maakte zich echter niet alleen zorgen om de weerstand van witte extremisten, maar juist om de weerstand onder witte liberalen: "They are uneasy with injustice but unwilling yet to pay a significant price to eradicate it." (...) "Over the last few years I have felt that their most troublesome adversary was not the obvious bigot of the Ku Klux Klan or the John Birch Society, but the white liberal who is more devoted to "order" than to justice, who prefers tranquility to equality" (King, 1967: 93)

Kritiek van de Black Power beweging

Martin Luther King Jr. schreef het boek in 1967, een periode na de overwinningen van de Civil Rights Act (1964) en Voting Rights Act (1965). Na een decennium geweldloze strijd hadden zwarte mensen op papier eindelijk gelijke rechten en kansen. In de praktijk zette de segregatie, onderdrukking en ongelijkheid zich echter voort en op bepaalde vlakken was het zelfs verergerd. Mede vanwege het gebrek aan verandering ondanks de politieke overwinningen van de burgerrechtenbeweging, en het aanhoudende geweld raakte vele zwarte activisten teleurgesteld. Velen begonnen de strategie van geweldloos verzet in twijfel te trekken. In het tweede hoofdstuk van het boek beschrijft King de intense discussies die hij met o.a. Stokely Carmichael voerde. Carmichael en zijn medestanders zagen het nut van geweldloos verzet niet meer in en pleitten voor een visie gebaseerd op de slogan 'Black Power'. Zo zei Carmichael het volgende: “Dr. King's policy was that nonviolence would achieve the gains for black people in the United States. His major assumption was that if you are nonviolent, if you suffer, your opponent will see your suffering and will be moved to change his heart. That's very good. He only made one fallacious assumption: In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.” In plaats van de focus op veranderen van het gedrag van de witte meerderheid moesten zwarte mensen zich volgens Black Power sympathisanten richten op het verkrijgen van politieke en economische macht. Bovendien zouden zwarte mensen bereid moeten zijn om zichzelf te verdedigen, zo nodig met geweld. Hoewel King zich kon vinden in de roep om politieke en economische macht te vergaren noemde hij Black Power een "nihilistische en onrealistische" visie. Zwarte mensen vormden een minderheid binnen de Verenigde Staten dus hij vond het onrealistisch om te denken dat zwarte mensen zich volledig konden separeren van witte mensen. De VS was een multi-etnische staat was waarin de verschillende groepen onlosmakelijk met elkaar verbonden waren én van elkaar afhankelijk waren. Bovendien vond King dat zwarte mensen een gewelddadige strijd tegen witte extremisten nooit zouden kunnen winnen omdat zei de politie, het leger en de staat achter zich hadden staan. Een gewelddadige strijd zou een vicieuze cirkel van haat en geweld opwekken, aldus King. Naast deze praktische argumenten was King geweldloos verzet op basis van zijn visie op liefde een fundamenteel aspect van zijn filosofie en levenswijze: "Returning violence for vilence merely multiplies violence, adding deeper darkess to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hare: only love can do that" (King, 1967: 64).

The Radical King

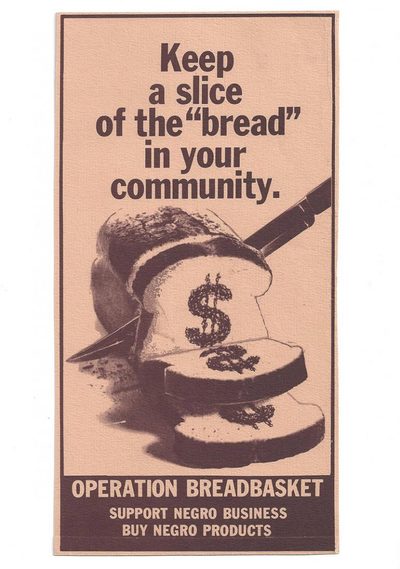

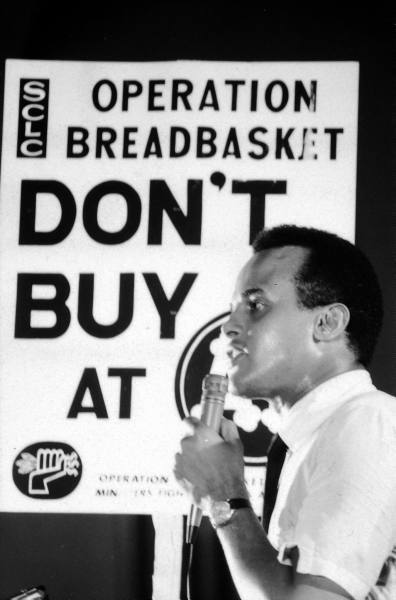

In "The Radical King" beschrijft dr. Cornel West hoe in mainstream media en educatie een bepaald beeld van dr. King is geconstrueerd dat hem reduceert tot een gemodereerde leider wiens visie was beperkt tot raciale integratie op basis van de befaamde "I have a dream speech". In werkelijkheid had dr. King een veel radicalere visie die hij constant verder ontwikkelde. Dr. King had serieuze kritiek op de manier waarop het kapitalistische systeem armoede onder zowel zwarte als witte mensen reproduceerde. Daarnaast had hij stevige kritiek op het militarisme van de VS dat in de jaren '60 een gewelddadige oorlog voerde in Vietnam. De drie grootste problemen van de VS noemende hij ook wel de "triple evils" van racisme, militarisme en armoede. King kon zich daarom wel vinden in de noodzaak om politieke invloed te winnen en economische macht op te bouwen. Zo beschreef hij in de gelijknamige speech "Where do we go from here" het interessante voorbeeld van "Operation Breadbasket". Dat was een programma van de burgerrechtenbeweging waarin ze afspraken om alle bedrijven die zwarte mensen discrimineerden en waar zwarte mensen in ondervertegenwoordigd waren te boycotten. "If you respect my dollar you must respect my person" zei King. Ze zetten bedrijven onder druk om te investeren in zwarte bedrijven en wijken zodat de economie in de zwarte achterwijken gestimuleerd konden worden. Met het programma wisten ze 2000 banen te scheppen en €15 miljoen aan inkomen binnen de zwarte gemeenschap in Chicago te genereren.

Een veranderd discours

Een ding kunnen we denk ik wel vaststellen: tien jaar geleden keek men je aan alsof je gek was als je durfde te zeggen dat er ook in Nederland sprake is van racisme. Ik durf te beweren dat de protesten (o.a. tijdens de nationale intochten) tegen zwarte piet essentieel zijn geweest om het publieke debat te doen kantelen en de keerzijde van de witte onschuld te openbaren. Na de gebeurtenissen rondom het zwarte piet debat: de emotionele racistische reacties van witte Nederlanders, de vele bedreigingen aan het adres van bekende en minder bekende Nederlanders en afgelopen jaar de levensgevaarlijke wegblokkade kan niemand dat racisme ook nog diep geworteld is in de Nederlandse samenleving. Door het intellectuele werk van zwarte vrouwen zoals Gloria Wekker, Philomena Essed en Anousha Nzume ontwikkelt zich naast het groeiende bewustzijn ook een taal om institutioneel racisme en ongelijkheid in de Nederlandse context te duiden. Termen en concepten zoals witte onschuld, wit privilege, institutioneel racisme en intersectionaliteit worden op regelmatige basis in mainstream media besproken. Zo was Sylvana Simons onlangs te gast bij Buitenhof en nam ze de ruimte om deze kwesties uitgebreid te bespreken. De kans is klein dat dit tien jaar geleden zou hebben plaatsgevonden. Een van de lessen die ik in Atlanta leerde was dat de focus vaak op dr. King ligt als de Civil Rights Movement wordt besproken. Achter en naast dr. King stonden echter duizenden mannen én vrouwen die de ruggengraat vormden van de beweging. Met name de rol van zwarte vrouwen zoals Coretta Scott King, Ella Baker en Fannie Lou Hamer in deze bewegingen wordt echter vaak vergeten of gewist uit de geschiedenis. Onlangs ontvingen wij een donatie, een stapel Ebony magazines uit de jaren '80. Op één van de magazines staat een mooie coverstory over Coretta Scott King "The Untold Story of Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King". In 2015 gaf Sylvana Simons een lezing tijdens de Martin Luther King Day, het stond dat jaar in het teken van rol van vrouwen in de anti-racisme beweging. Drie jaar later kunnen we vaststellen dat zwarte vrouwen zoals Wekker, Simons en Nzume zich duidelijk laten horen en zien. Zij zijn de personen die het verhaal, de theorie en de taal van anti-racisme op een krachtige, elegante inhoudelijke en waardige manier weten te vertalen naar een breder publiek. Het wordt ze niet altijd in dank afgenomen maar de kans is klein dat ze uit de geschiedenis zullen worden geschreven. Achter deze zwarte vrouwen die prominent in de media voorkomen staan echter honderden andere zwarte vrouwen en vrouwen van kleur, en ook wat mannen, die zich dagelijks inzetten voor de hardnekkige strijd tegen racisme, een erfenis van honderden jaren kolonialisme en slavernij. Sommigen zoals Jessy, Chantelle, Devika en Kitty door hun tijd en energie op te offeren tijdens vreedzame protesten van Dokkum tot Rotterdam en anderen door constant in discussie te gaan met familie, met schoolbesturen, met collega's op de werkvloer en anderen die zich nog onder de mantel van witte onschuld verschuilen.

Where do we go from here?

De grote vraag die dr. King in 1967 stelde was “Where do we go from here?”. Ook voor de de anti-racisme beweging is dit een belangrijke vraag: Hoe gaan we verder en wat wordt de volgende stap? Heeft het nog nut om te blijven protesteren tijdens de (nationale) intochten of wordt het tijd voor andere acties? Moeten we ons minder richten op protest tegen en meer energie steken in het bouwen van eigen instituten ten behoeve van politieke en economische invloed? Wat is de rol van witte bondgenoten, hoe dealen we met anti-zwart racisme binnen andere gemeenschappen van kleur en creëer je solidariteit tussen verschillende gemeenschappen? Hoe zorgen we voor een beweging waarin andere vormen van onderdrukking zoals homofobie, transfobie, seksisme etc. ook de benodigde aandacht krijgen zonder dat een door witheid gedomineerde verwaterde versie van intersectionaliteit de boventoon gaat voeren? Hoe verbinden we de strijd tegen zwarte piet met andere vormen van institutioneel racisme én andere vormen van ongelijkheid en onderdrukking zoals het vluchtelingenvraagstuk en economische ongelijkheid op basis van het neoliberale kapitalisme? Dit zijn een paar complexe vragen waar over nagedacht dient te worden en waar ik het antwoord (nog) niet op heb. Op 14 januari gaan we in gesprek over de (toekomst van) de anti-racisme beweging in Nederland en deze vragen. Eerst tijdens de Martin Luther King dag, vervolgens tijdens de lezing met Gloria Wekker bij The Black Archives. Rondleidingen met thema Martin Luther King Jr. en de Civil Rights Movement In het kader van de Martin Luther King Day zullen we op zaterdag 13 en zondag 14 januari om half 1 speciale rondleidingen geven waarin we exclusieve archiefstukken over de Civil Rights Movement zullen tonen. Daarnaast kan je 2 x 2 kaarten winnen voor de uitverkochte lezing van Gloria Wekker op 14 januari. Stuur een kort essay of opiniestuk (max. 2000 woorden) over jouw visie op de toekomst van de anti-racisme beweging in Nederland en gebruik hiervoor het werk van Gloria Wekker en/of Martin Luther King Jr. Stuur dit uiterlijk vrijdag 12 januari om 17:00 op naar [email protected]. Op zaterdag 13 januari maken we de winnaars bekend.

Aanbevolen boeken:

- Martin Luther King Jr. - Where do we go from here - Martin Luther King Jr. The Radical King, edited by Cornel West - Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) and Charles V. Hamilton Black Power |

The Black Archives BlogArchieven

Juni 2024

|

Openingstijden/Opening TimesWoensdag/Wednesday 11.00 - 17.00 uur

Donderdag/Thursday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Vrijdag/Friday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Zaterdag/Saturday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Onze nieuwe locatie in Amsterdam Zuidoost is geopend. Neem contact op via de pagina contact voor rondleidingen buiten het programma. We moved to South East Amsterdam. Contact us via the page contact for tours outside our program. |

(Rolstoel)toegankelijkheid/Accessibility

Momenteel beschikt The Black Archives niet over een speciale ingang en lift voor personen met een fysieke beperking en voor rolstoelgebruikers.

At this moment, The Black Archives does not have a special entrance or lift for person of disability. |

RSS-feed

RSS-feed