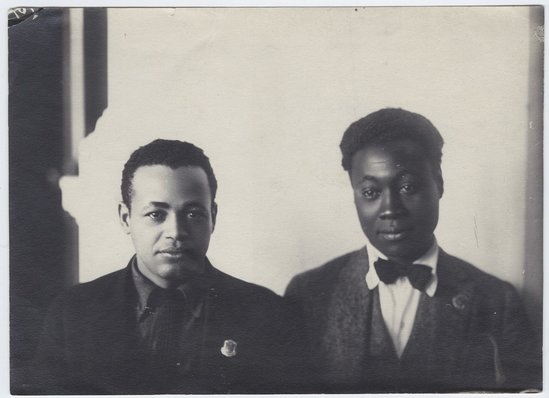

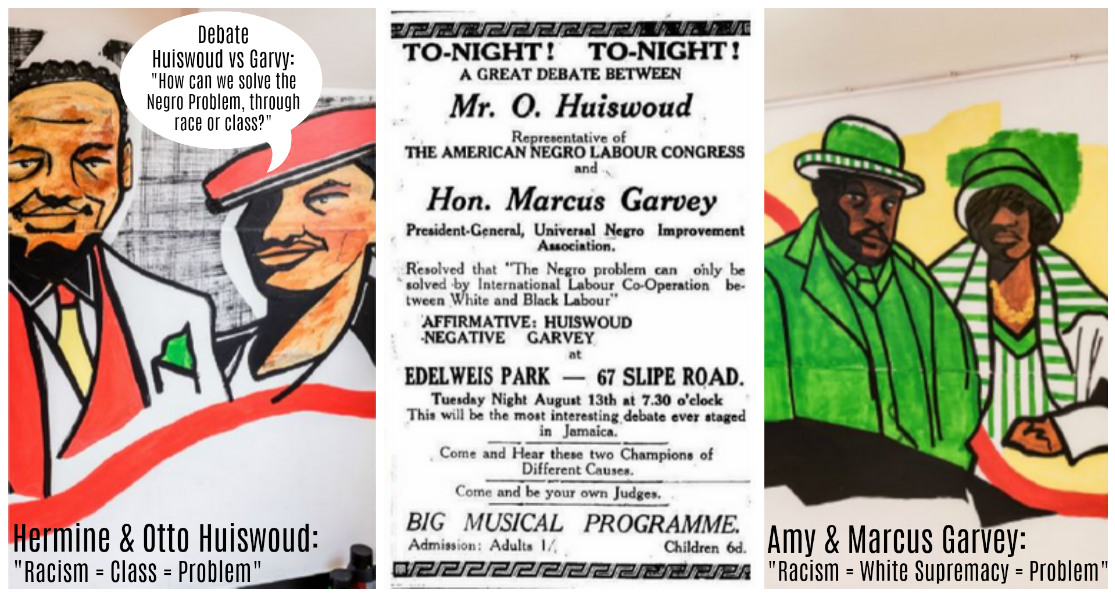

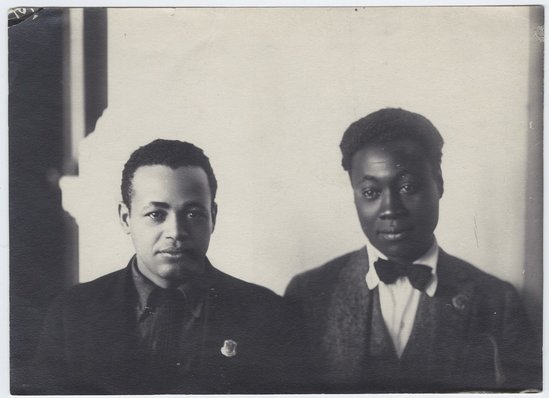

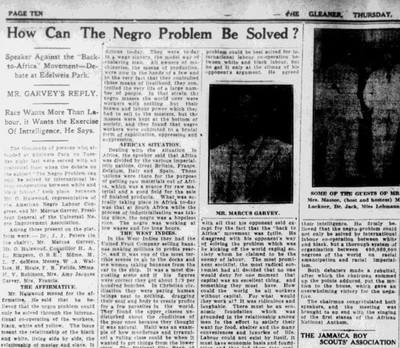

A hidden history of Pan-Africanism: the debate between Garvey and Huiswoud, is it still relevant?12/2/2020 This blog was originally written in Dutch and published on January 24th 2018 The discovery of a historic treasure: The Black Archives This week marks the two-year anniversary since we moved from the “Verhalenkamer” in North Amsterdam to the building of the “Ons Suriname” association (English: “Our Suriname”). To be exact, we entered this historic building on the 23rd of January 2016. In a room on the third floor of the building, we found a collection of books and documents. We did not know exactly what the documents contained, but the room was a big mess. It was full of old boxes and cabinets that, because of the thick layers of dust, gave the impression that they had fallen into oblivion in recent decades. However, we urgently needed space for our books so we made a deal with the association: If we helped them clean up the space, we could place our books alongside their documents. However, while we were busy bringing order to the chaos, we came across extraordinary books and documents. A Time magazine from 1963 with James Baldwin on the cover, program booklets by Keti Koti, emancipation commemorations from the 50's and when we found a book by the famous poet Langston Hughes with his signature, we realized we had stumbled upon a treasure. Many of the treasures came from boxes with the name 'Huiswoud' written on them. Part of the collection appeared to have been collected by Hermine and Otto Huiswoud. This is how our search for the origin of these archival documents and the extraordinary story of the Huiswouds began. A search for the story of Hermine and Otto Huiswoud: Forgotten black revolutionaries Otto Huiswoud was born in 1893. His father had worked as an enslaved person under the Dutch colonial rule. Otto was a curious boy and, at the age of sixteen, he ended up as a student of a captain on a ship that had the Netherlands as its final destination. However, he would not reach this final destination immediately because he would first come ashore in New York. In New York, he soon came into contact with socialist literature and people who were politically active like Hubert Harrison, an African American with roots in the Caribbean island of St. Croix who came to be known as "the Voice of Harlem Radicalism”. It did not take long before Huiswoud himself became politically active. In 1919 he was the only black co-founder of the Communist Party of America (CPUSA). The party was founded shortly after the Russian Revolution, when the socialist party split up. Otto was also active in the African Blood Brotherhood, a black militant organization that aimed to improve the position of African Americans. Hermina Huiswoud was born in British Guiana in 1905 and migrated with her family to New York in 1919. Otto and Hermina met in New York and would spend the rest of their lives together. In 1922 Otto travelled as a delegate on behalf of the CPUSA to the Fourth World Congress of the Comintern in Moscow. Together with the Jamaican poet Claude McKay, he worked to get what they called the “Negro Question" on the party's agenda. Black communists and “the Negro question” Many black activists, such as the Huiswouds and McKay, drew inspiration from communist ideology and the October Revolution in Russia of 1917. Communists pursued a world revolution in which workers would overthrow the imperial powers and the system of capitalism. Based on socialist theory, black communists argued that "the Negro question"- the oppression of people of African origin around the world - was fundamentally an economic problem in which black people were used as a source of cheap labor by the capitalist class. [1] For example, Huiswoud argued at the congress in Moscow: “Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way back in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way back in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” – Huiswoud, 1922 They saw organizing and mobilizing black people in the U.S. and colonies in Africa and the Caribbean as an essential step to bringing about the world revolution. In addition, they saw solidarity between black and white workers as a necessary means for orchestrating this revolution. However, competition between workers and the legacy of slavery that spread into vicious forms of racism and discrimination divided the working class according to black communists. For example, black workers were often not admitted to unions, were paid less for the same work and there was segregation of various public and private facilities such as schools, buses and swimming pools. During this period, racism was violent and manifested itself in the lynching practices that systematically terrorized black communities. It was a period during which white supremacy took explicit and violent forms in the US and European powers had most of the African continent, South America and the Caribbean under colonial control. A more subtle form of racism was also present in the North of the US. Practices such as exclusion in the labor market and the housing market were widespread. There was little organized resistance. After all, resistance was dangerous. Watch this lecture by Dr. Hakim Adi, author of the book Pan-Africanism & Communism Click here to edit. Marcus Garvey and de UNIA Although many black radicals who wanted to fight for freedom found their salvation in communism, there were also other ideas and movements. The most prominent black emancipation movement that emerged in the same period was the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) led by Marcus Garvey. Garvey had already started in Jamaica but founded a division in the United States in the same year that the October Revolution took place in 1917. A direct cause was the bloody "East St. Louis riot" in which 40 black Americans were killed by racist violence caused by a conflict between black and white workers. White workers were afraid that black workers would take over their jobs in the aluminum industry. [1] Unlike the black communists, Garvey did not believe that "the Negro Question" was fundamentally an economic issue of class struggle that required solidarity with white workers. Garvey held the idea of “race first”. As an advocate of black nationalism, he believed that black people could be emancipated by pursuing political, economic and cultural independence. “Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad” was his motto. With the famous Black Star shipping line, he aimed to promote trade between different black communities and through the newspaper "the Negro World" he managed to reach millions of black people. Garvey is seen as one of the icons of Pan-Africanism, an ideology and movement based on the idea that people of African origin have common interests worldwide and therefore need to unite. Watch a documentary about Marcus Garvey here: Garvey's UNIA has had the largest mass movement of black people in history so far, at its peak the movement had an estimated one million members in the US, Caribbean and Europe. Because of personal and political circumstances, including fierce battles with black communists and security services, the influence of Garvey and the UNIA declined relatively quickly. He was convicted of fraud in 1923 and deported to Jamaica in 1927. The UNIA never recovered, but Garvey's immense ideological influence has been evident in the vision of black emancipation movements to this day. His words are immortalized in Bob Marley's famous song, Redemption song:"Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds!” The black star on the Ghanaian flag is co-inspired by Garvey's Black Star line. Although Garvey did not pursue a world revolution like the black communists, his vision and movement revolutionized the minds of many black people who, after centuries of racist indoctrination, learned to be proud of themselves, their skin color and their African background. The big debate: Garvey vs. Huiswoud During our research we came to the extraordinary discovery that Huiswoud and Garvey knew each other. Although they both pursued the emancipation of black people, they had opposing views on how emancipation could be realized. In 1929 Otto and Hermina visited a number of Caribbean and South American countries on behalf of the Comintern: Trinidad, Haiti, Colombia, Suriname, British Guiana and Jamaica. In Jamaica, a UNIA congress, which Garvey tried to revive, took place during the same period. Huiswoud saw this as an opportunity to challenge Garvey to a public debate in the lion's den: In Garvey’s homeland and during his own congress. Garvey accepted the debate. The debate was announced in the Jamaican newspaper “the Gleaner”. Huiswoud would defend the following statement: "The Negro problem can only be solved by International Labor Co-Operation between White and Black Labor". Garvey was against it. In an account of the debate in the same newspaper a few days later, entitled "How can the Negro problem be solved?", the vision of Huiswoud and the black communists was clearly described: “Mr. Huiswoud moved for the affirmative. He said that he believed that the negro problem could only be solved through international cooperation of the workers, black, white and yellow the issue meant the relationship of the black and white, living side by side, the relationship of master and slave. It was an exploitation of negroes by the white ruling class with the only one object in view the securing of super-profits. (…) The Negro problem was definitely a class problem, fundamentally a class one and not a race one, for race served to intensify the situation, and gave an impetus to the further exploitation of the negro.” Garvey, on the other hand, defended his position that black people should not only focus on labor but also to raise capital so that their own empire could start. Garvey won the debate, but according to archival documents, Huiswoud managed to win over a number of people. He returned a year later, in 1930, to meet black workers but was seen by the authorities as a "communist agitator" and was heavily opposed. In 2018, we aim to investigate this debate and the various movements in the black radical tradition. Relevance of the debate

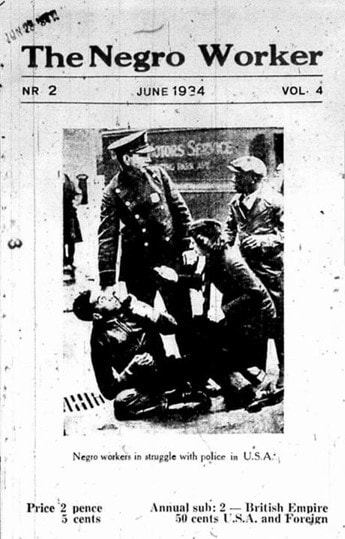

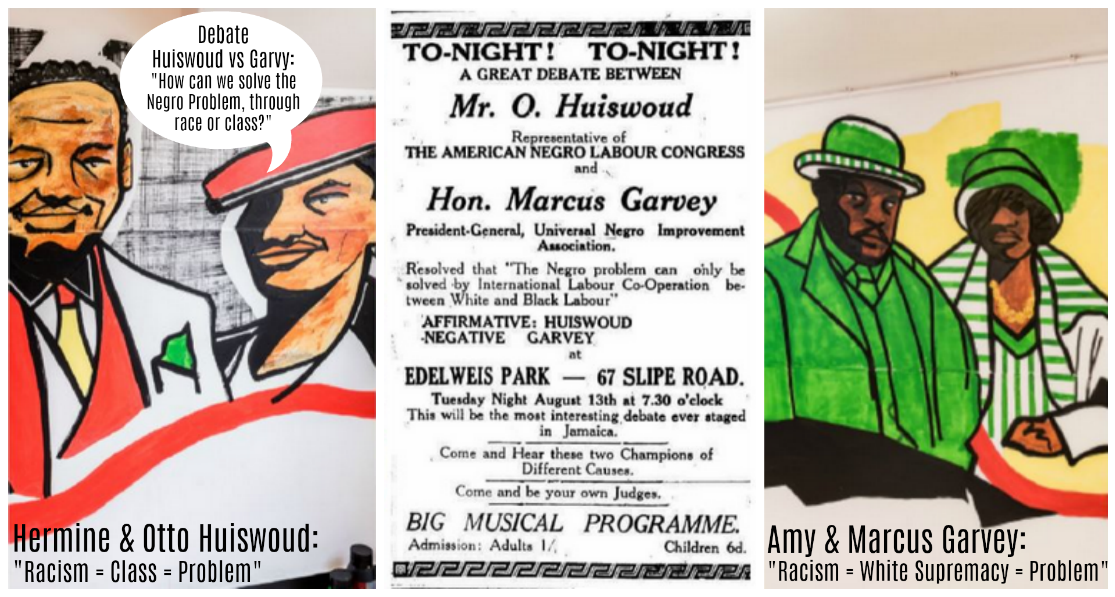

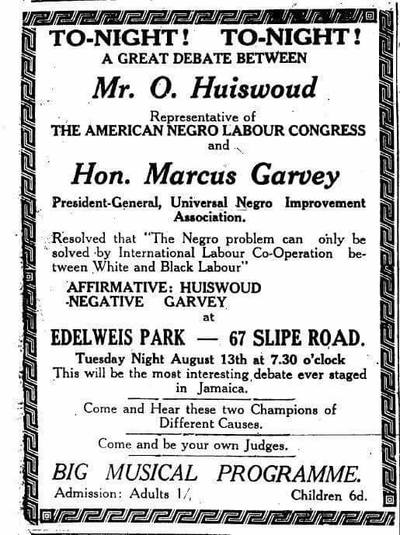

Although the debate between Garvey and Huiswoud took place 90 years ago (1927), the issue of "the Negro Question" is still very relevant in 2017. Worldwide, from the African continent, to the United States, Europe and the Caribbean, the majority of people of African origin are at the bottom of the social ladder. On a daily basis, people of African origin are still being dehumanized with the modern form of slavery in Libya and the countless Africans who die during their crossing from the continent to Europe as tragic lows. Despite the fact that certain goals, from both Huiswoud and Garvey, have been achieved, the vast majority of people of African origin live in appalling conditions. After the wave of decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s, in which both black nationalism and communist-inspired emancipation movements played an important role, most African and Caribbean countries became politically independent. Economically, however, many countries are still in a dependent position where raw materials are exploited by western companies that make large profits while the majority of the population does not benefit from them. Politically, in most African and Caribbean countries, "black leaders" are in power, but the old colonial power structures seem to have remained unchanged under their rule. In many Caribbean and African countries, a powerful class of black people has emerged. In many cases, there is a small group that enjoys the wealth while the masses live in poverty or have to die with very limited resources. For example, research showed that there are more than 160,000 people who own assets of more than $1 million while gross national income per capita is still relatively low and about half of the children in the sub-Saharan region live on $1.90 a day. [1] [2] The average income in 'Western' countries is higher, which reduces extreme poverty, but income and wealth inequality is still huge. Researchers say it would take 228 years to close the wealth disparity between black and white families in the US. [3] In the New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander describes how, despite the accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement, a significant portion of the African American population is stuck in a "racial underclass". Despite the fact that an upper class of wealthy African Americans has emerged, the system of mass incarceration, "the New Jim Crow" perpetuates racial inequality. There are currently more African Americans in prison or probation than there were enslaved in 1850, and a quarter of the African American population lives below the poverty line. Although the extreme wealth and income inequality in the Netherlands is less severe than in the US and extreme poverty is rare, there is also racial inequality here. According to CBS,12% of Surinamese Dutch and 20% of Caribbean Dutch people live in poverty compared to 5% of people of Dutch origin. The figures are harder to find about people from the African continent. During our study trip, the events in Charlottesville once again reminded us in a violent way that the problem of white supremacy is not yet a thing of the past. On the contrary, the racism and white supremacy that was so openly displayed in the days when Huiswoud and Garvey were alive seems to have made a comeback. "The Negro Question" is as relevant as it was 90 years ago, but what can we learn from the lives of the various movements that have fought? Who was right from a historical perspective, Garvey, Huiswoud or was there in each of their visions a kernel of truth? How is it that many of us know Garvey but have never heard of Huiswoud and

2 Opmerkingen

Door: Mitchell Esajas* De vondst van een historische schat: The Black Archives Deze week is het exact twee jaar geleden dat wij van de Verhalenkamer in Amsterdam-Noord verhuisden naar het pand van Vereniging Ons Suriname. Op 23 januari 2016, om precies te zijn, betraden wij dit historische pand. In een ruimte op de derde verdieping van het pand scheen ook een collectie boeken en documenten te liggen. Wat er precies lag wisten we niet, de ruimte was echter een grote chaos. Het lag vol met oude dozen en kasten die door de dikke lagen stof de indruk gaven dat ze de afgelopen decennia in de vergetelheid waren geraakt. We hadden echter dringend ruimte nodig voor onze boeken dus we maakten een deal met de vereniging: als hij hen hielpen de ruimte op te ruimen konden wij onze boeken erbij plaatsen. Terwijl we bezig waren orde in de chaos te scheppen kwamen we echter bijzondere boeken en documenten tegen. Een oude Time magazine uit 1963 met James Baldwin op de cover, programma boekjes van Keti Koti emancipatie herdenkingen uit de jaren ’50 én toen we een boek van de beroemde poet Langston Hughes met zijn handtekening vonden wisten we dat we een schat hadden gevonden. Veel van de schatten kwamen uit dozen waar de naam ‘Huiswoud’ op stond geschreven. Een deel van de collectie bleek verzameld te zijn door Hermine en Otto Huiswoud. Zo begon onze zoektocht naar de herkomst van deze archiefstukken en het uitzonderlijke verhaal van de Huiswouds.

Een zoektocht naar het verhaal van Hermine en Otto Huiswoud: vergeten zwarte revolutionairen Otto Huiswoud is geboren in 1893, zijn vader heeft nog als tot slaaf gemaakte moeten werken onder het Nederlandse koloniale bewind. Otto was een nieuwsgierige jongen en belandde op zestienjarige leeftijd als matroos in de leer van een kapitein op een schip dat Nederland als eindbestemming had. Hij zou deze eindbestemming echter niet direct bereiken omdat hij in New York aan wal trad. In New York kwam hij al snel in aanraking met socialistische literatuur en mensen die politiek actief waren zoals Hubert Harrison, een Afro-Amerikaan met wortels in het Caribische eiland St. Croix die bekend kwam te staan als “the Voice of Harlem Radicalism”. Het duurde niet lang totdat Huiswoud zelf ook politiek actief werd. In 1919 was hij de enige zwarte medeoprichter van de Communist Party of America (CPUSA). De partij ontstond toen er na de Russische Revolutie een splitsing gebeurde binnen de socialistische partij. Ook Otto actief in de African Blood Brotherhood, een militante zwarte organisatie die als doel had om de positie van Afro-Amerikanen te verbeteren. Hermina werd geboren in 1919 in Brits-Guyana en migreerde in 1919 met haar familie naar New York. Otto en Hermina ontmoetten elkaar in New York en zouden de rest van hun leven met elkaar delen. In 1922 reisde Otto als afgevaardigde namens de CPUSA naar het Vierde Wereldcongres van de Comintern in Moskou. Samen met de Jamaicaanse poet Claude McKay spande hij zich in om wat zij “the Negro Question” noemden op de agenda van de partij te krijgen. Otto Huiswoud en Claude McKay, 1922 in Moskou Zwarte communisten en “the Negro question” Vele zwarte activisten, zoals de Huiswouds en McKay, haalden inspiratie uit de Oktoberevolutie in Rusland van 1917 en uit communistische ideologie. Communisten streefden een wereldrevolutie na waarin arbeiders de imperiale machten en het systeem van kapitalisme omver zouden werpen. Op basis van socialistische theorie stelden zwarte communisten dat “the Negro question”, de onderdrukking van mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst in de hele wereld, fundamenteel een economisch probleem was waarin zwarte mensen als een bron van goedkope arbeid werden gebruikt door de kapitalistische klasse.[1] Zo betoogde Huiswoud het volgende tijdens het congres in Moskou: “Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way back in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” Although the Negro problem as such is fundamentally an economic problem, notwithstanding, we find that this particular problem is aggravated and intensified by the friction which exists between the white and black races. It is a matter of common knowledge that prejudice as such, although born from the class prejudice that any group takes in society, notwithstanding the question of race, does play an important part. Whilst it is true that, for instance, in the United States of America the main basis of racial antagonism lies in the fact that there is competition of labor in America between black and white, nevertheless, the Negro bears a badge of slavery on him which has its origin way bak in the time of his slavery. Hence you find that this particular antagonism on the part of the white workers to the black workers assumes this particular form because of this very fact.” – Huiswoud, 1922 Otto Huiswoud, Langston Hughes en een Afro-Amerikaanse delegatie in de Sovjet Unio in de jaren '30 Het organiseren en mobiliseren van zwarte mensen in de VS en kolonies in Afrika en het Caribisch gebieden zagen ze als een essentiële stap om de wereldrevolutie tot stand te brengen. Daarnaast zagen ze solidariteit tussen zwarte en witte arbeiders als een noodzakelijk middel om te revolutie tot stand te brengen. Concurrentie tussen de arbeiders en de erfenis van slavernij dat zich uitte in vicieuze vormen racisme en discriminatie verdeelde de arbeidersklasse echter volgens zwarte communisten. Zo werden zwarte arbeiders vaak niet toegelaten tot vakbonden, kregen ze minder betaald voor het zelfde werk en was er sprake van segregatie verschillende publieke en private voorzieningen zoals scholen, bussen en zwembaden. Het racisme uitte zich in deze periode op zeer gewelddadige manier door de lynchpraktijken waarmee zwarte gemeenschappen stelselmatig geterroriseerd werden. Het was een periode waarin witte suprematie expliciete en gewelddadige vormen aan nam in de VS en waarin Europese mogendheden het grootste deel van het Afrikaanse continent, Zuid-Amerika en het Caraïbische gebied onder koloniale controle had. Het vond echter ook plaats in de vorm van subtielere vormen van racisme zoals uitsluiting op de arbeidsmarkt en de woningmarkt in het Noorden van de VS. Er was nog weinig sprake van georganiseerd verzet, verzet was immers levensgevaarlijk. Bekijk hier een lezing van dr. Hakim Adi, auteur van het boek Pan-Africanism & Communism De Russische revolutie en de communistische visie dat een eeuwenoud imperium omver had geworpen en openlijk opriep tot bevrijding van alle onderdrukte volkeren bood voor vele zwarte activisten dan ook een aanlokkelijk vergezicht. Zwarte radicalen zagen de wereldrevolutie als een kans om zichzelf en de gekoloniseerde gemeenschappen waar ze uit voortkwamen te bevrijden. Huiswoud was één van de vele zwarte radicalen die zich in deze periode aansloot bij de Communistische beweging om de strijd aan te gaan voor de wereldrevolutie. In de periode voor de Tweede Wereldoorlog wist hij, tezamen met zijn vrouw Hermina, een prominente carrière als professioneel revolutionair op te bouwen waarbij hij onder meer de wereld rond rees om zwarte vakbondsbewegingen op te zetten en met elkaar te verbinden. Zo werd Otto, nadat George Padmore uit de partij was gezet, voorzitter van de International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW). Als redacteur van hun blad, the Negro Worker, had Otto contact met zwarte activisten in de VS, Europa, het Afrikaanse continent, het Caraïbische gebied en in Latijns-Amerika. Zo schreef Anton de Kom in 1923 een artikel getiteld “Starvation, Misery and Terror in Dutch Guiana". Ook stonden er boeiende artikelen in over de Scottsboro Case, de Congo, de invasie van Ethiopië door de Italianen en meer. Marcus Garvey en de UNIA Hoewel vele zwarte radicalen wilden strijden voor vrijheid hun heil vonden in het communisme waren er ook andere visies, stromingen en bewegingen. De voornaamste zwarte emancipatie beweging die in dezelfde periode opkwam was de Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) onder leiding van Marcus Garvey. Garvey was reeds in Jamaica begonnen maar richtte in hetzelfde jaar dat de Oktoberrevolutie plaatsvond, in 1917, een divisie in de Verenigde Staten op. Een directe aanleiding was de bloedige “East St. Louis riot” waarbij 40 zwarte Amerikanen door racistisch geweld waren omgekomen, nota bene vanwege een conflict tussen zwarte en witte arbeiders. Witte arbeiders waren bang dat zwarte arbeiders hun banen in de aluminium industrie zouden overnemen.[1] In tegenstelling tot de zwarte communisten geloofde Garvey niet dat “the Negro Question” fundamenteel een economische kwestie van klassenstrijd was waarbij solidariteit met witte arbeiders vereist was. Bij Garvey stond “race first”, als voorvechter van zwart nationalisme geloofde hij dat zwarte mensen geëmancipeerd konden worden door politieke, economische en culturele onafhankelijkheid na te streven. “Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad” was zijn motto. Met de fameuze Black Star shipping line beoogde hij de handel tussen verschillende zwarte gemeenschappen te bevorderen en middels de krant “the Negro World” wist hij miljoenen zwarte mensen te bereiken. Garvey wordt gezien als één van de iconen van het Pan-Afrikanisme, een ideologie en beweging gebaseerd op het idee dat mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst wereldwijd gezamenlijke belangen hebben en zich daarom dienen te verenigen. [1] Ida B Wells schreef hierover? The renowned journalist Ida B. Wells reported in The Chicago Defender that 40–150 African-American people were killed during July in the rioting in East St. Louis.[14][18] The NAACP estimated deaths at 100–200. Six thousand African-Americans were left homeless after their neighborhood was burned. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_St._Louis_riots Bekijk hier een documentaire over Marcus Garvey: Garvey’s UNIA heeft tot nu toe de grootste massabeweging van zwarte mensen in de geschiedenis gehad, op het hoogtepunt had de beweging naar schatting een miljoen leden in de VS, het Caribische gebied en Europa. Wegens persoonlijke én politieke omstandigheden, waaronder felle strijd met zwarte communisten en veiligheidsdiensten, zijn Garvey en de UNIA relatief snel weer ten onder gegaan. Hij werd in 1923 veroordeeld wegens fraude en in 1927 naar Jamaica gedeporteerd. De UNIA is er nooit bovenop gekomen maar de immense ideologische invloed van Garvey is tot vandaag de dag zichtbaar geweest in de visie van zwarte emancipatiebewegingen. Zijn woorden zijn vereeuwigd in het bekende lied van Bob Marley, Redemption song: "Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds!” De zwarte ster op de Ghanese vlag is mede-geïnspireerd door de Black Star line van Garvey. Hoewel Garvey geen wereldrevolutie nastreefde zoals de zwarte communisten heeft zijn visie en beweging voor een revolutie in de geest van vele zwarte mensen gezorgd die na eeuwenlange racistische indoctrinatie leerden trots op zichzelf, hun huidskleur en hun Afrikaanse achtergrond te zijn. Muurschilderingen van Brian Elstak / Foto's: Maartje Strijbis Het grote debat: Garvey vs. Huiswoud Tijdens ons onderzoek kwamen tot de bijzondere ontdekking dat Huiswoud en Garvey elkaar kenden. Hoewel ze allebei de emancipatie van zwarte mensen nastreefden hadden ze tegengestelde visies op de manier waarop de emancipatie gerealiseerd kon worden. In 1929 bezochten Otto en Hermina in opdracht van de Comintern een aantal Caribische en Zuid-Amerikaanse landen: Trinidad, Haiti, Colombia, Suriname, Brits-Guyana én Jamaica. In Jamaica vond in dezelfde periode een congres van de UNIA, die Garvey nieuw leven in probeerde te blazen, plaats. Huiswoud zag de kans schoon om Garvey tot een publiek debat uit te dagen in het hol van de leeuw, in zijn thuisland en tijdens zijn eigen congres. Garvey accepteerde het debat. Het debat werd groots aangekondigd in de Jamaicaanse krant, the Gleaner. Huiswoud zou de volgende stelling verdedigen: “The Negro problem can only be solved by International Labour Co-Operation between White and Black Labour". Garvey stond er tegen over. In een verslag van het debat in dezelfde krant enkele dagen later, getiteld “How can the Negro problem be solved?”, stond de visie van Huiswoud en de zwarte communisten duidelijk beschreven: “Mr. Huiswoud moved for the affirmative. He said that he believed that the negro problem could only be solved through international cooperation of the workers, black, white and yellow The issue meant the relationship of the black and white, living side by side, the relationship of master and slave. It was an exploitation of negroes by the white ruling class with the only one object in view the securing of super-profits. (…) The Negro problem was definitely a class problem, fundamentally a class one and not a race one, for race served to intensify the situation, and gave an impetus to the further exploitation of the negro.” Garvey verdedigde daarentegen zijn positie dat zwarte mensen zich niet slechts moesten richter op arbeid maar ook kapitaal moesten vergaren zodat hun eigen imperium konden starten. Garvey won het debat maar volgens archiefstukken wist Huiswoud in het hol van de leeuw toch een aantal mensen voor zich te winnen. Hij keerde een jaar later, in 1930, terug om zwarte arbeiders te ontmoeten maar werd door de autoriteiten als “communist agitator” gezien en tegengewerkt. In 2018 beogen wij nader onderzoek te doen naar dit debat en de verschillende stromingen in de zwarte radicale traditie. De relevantie van het debat Hoewel het debat tussen Garvey en Huiswoud 90 jaar geleden, in 1927, plaatsvond is het vraagstuk, “the Negro Question”, anno 2017 nog erg relevant. Wereldwijd, van het Afrikaanse continent, tot de Verenigde Staten, Europa en het Caraïbische gebied, bevindt het gros van de mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst zich aan de onderkant van de maatschappelijke ladder. Op dagelijkse basis worden mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst nog gedehumaniseerd met de moderne vorm van slavernij in Libië en de talloze Afrikanen die de dood vinden tijdens hun overtocht van het continent naar Europa als tragische dieptepunten. Ondanks het feit dat bepaalde doelen, van zowel Huiswoud als Garvey, zijn gerealiseerd leeft het overgrote deel van de mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst onder erbarmelijke omstandigheden. Na de dekolonisatiegolf in de jaren ’50 en ’60, waarin zowel zwart nationalisme als communistische geïnspireerde emancipatiebewegingen een belangrijke rol speelden, zijn de meeste Afrikaanse en Caraïbische landen politiek onafhankelijk geworden. Economisch gezien zijn vele landen echter nog in een afhankelijke positie waarin grondstoffen worden geëxploiteerd door westerse bedrijven die grote winsten maken terwijl het gros van de bevolking er niet van profiteert. Politiek gezien zijn in de meeste Afrikaanse en Caribische landen “zwarte leiders” aan de macht, maar de oude koloniale machtsstructuren lijken ook onder hun bewind weinig verandert te zijn. In vele Caraïbische en Afrikaanse landen is er weliswaar een kapitaalkrachtige klasse van zwarte mensen ontstaan. In vele gevallen is er een kleine groep die van de rijkdom geniet terwijl de massa in armoede leeft of met zeer beperkte middelen moet zien te overleden. Zo bleek uit onderzoek dat er meer dan 160,000 mensen zijn die een vermogen van meer dan $1 miljoen bezitten terwijl het bruto nationaal inkomen per hoofd nog relatief laag is en ongeveer de helft van de kinderen in de regio onder de Sahara in extreme armoede, $1.90, per dag leven.[1] [2] Het gemiddelde inkomen in ‘westerse’ landen is hoger waardoor extreme armoede minder voorkomt maar de inkomens- en vermogensongelijkheid is nog gigantisch. Volgens onderzoekers zou het 228 jaren duren om de kloof in vermogensongelijkheid tussen zwarte en witte gezinnen in de VS te dichten.[3] In the New Jim Crow beschrijft Michelle Alexander hoe, ondanks de overwinningen van de Civil Rights Movement, een aanzienlijk deel van de Afro-Amerikaanse bevolking vast zit in een “raciale onderklasse”. Ondanks het feit dat er een bovenklasse van vermogende Afro-Amerikanen is ontstaan reproduceert het systeem van massa-incarceratie, “the New Jim Crow” raciale ongelijkheid in stand. Er zijn momenteel meer Afro-Amerikanen in de gevangenis of in de reclassering dan dat er in 1850 tot slaaf gemaakt waren en een kwart van de Afro-Amerikaanse bevolking leeft onder de armoedegrens. Hoewel de extreme vermogens- en inkomensongelijkheid in Nederland minder sterk is dan in de VS en extreme armoede nauwelijks voorkomt is er ook hier sprake van raciale ongelijkheid. Zo leeft, volgens het CBS, 12% van de Surinaamse Nederlanders en 20% van de Caraïbische Nederlanders in armoede ten opzichte van 5% van de mensen van Nederlandse origine. Over mensen van het Afrikaanse continent zijn de cijfers minder makkelijk te vinden. Tijdens onze studiereis werden we door de gebeurtenissen in Charlottesville wederom op een gewelddadige manier herinnert dat het probleem van witte suprematie nog niet tot het verleden behoort. Integendeel, het racisme en de witte suprematie dat zo openlijk getoond werd in de tijd dat Huiswoud en Garvey leefden lijkt een comeback te hebben gemaakt. “The Negro Question” is net zo relevant als 90 jaar geleden maar wat kunnen we leren van de levens van de verschillende bewegingen die hebben gestreden? Wie had gelijk vanuit historisch perspectief, Garvey, Huiswoud of zat er in elk van hun visies een kern van waarheid? Hoe komt het dat velen van ons Garvey wel kennen maar nog nooit van Huiswoud hebben gehoord en wat is de legacy van Hermine en Otto Huiswoud in Nederland? De komende maanden gaan wij verder met ons onderzoek naar Hermine en Otto Huiswoud. Op 27 januari zal historicus Hakim Adi een lezing geven op basis van zijn boek Pan-Africanism and Communism waarin onder meer het debat tussen Garvey en Huiswoud is belicht. Bezoek voor meer informatie onze website www.theblackarchives.nl. * Een andere versie van dit artikel werd eerder gepubliceerd via IISR. Lees hier de reactie van Sandew Hira.

Read more: |

The Black Archives BlogArchieven

Juni 2024

|

Openingstijden/Opening TimesWoensdag/Wednesday 11.00 - 17.00 uur

Donderdag/Thursday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Vrijdag/Friday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Zaterdag/Saturday 11.00 - 17.00 uur Onze nieuwe locatie in Amsterdam Zuidoost is geopend. Neem contact op via de pagina contact voor rondleidingen buiten het programma. We moved to South East Amsterdam. Contact us via the page contact for tours outside our program. |

(Rolstoel)toegankelijkheid/Accessibility

Momenteel beschikt The Black Archives niet over een speciale ingang en lift voor personen met een fysieke beperking en voor rolstoelgebruikers.

At this moment, The Black Archives does not have a special entrance or lift for person of disability. |

RSS-feed

RSS-feed